By John McDonough

In the late 1980s Dick Cavett asked pianist Oscar Peterson a rather startling question: “How good a trumpet player was Louis Armstrong?”

Peterson seemed surprised at the question. His friendly smile suddenly turned dead serious. “Fantastic,” he said. “Fantastic.”

Peterson was right, but he shouldn’t have been surprised. Armstrong had been dead for nearly 20 years by then. Most Americans remembered him for “Hello Dolly,” and younger listeners knew him only as the legendary “Satchmo,” whose recording of “What a Wonderful World” was used so ironically in the 1987 film Good Morning Vietnam. But Cavett wouldn’t have needed to ask the question at all had he gone to Ravinia for Armstrong’s debut performance on July 16, 1956. Fortunately, I did go.

The timing was perfect. I had just graduated from 8th grade that summer, and I was old enough to realize that such accredited life passages demand a commemorative reward of princely proportions. Unlike many of my friends, I had no interest at all in seeing Elvis Presley. So instead I extorted from my parents a trip to Ravinia to see Armstrong. By today’s standards, it would barely qualify as pocket change; a reserved seat in the Pavilion in those days’ dollars was only $3. I also felt a certain urgency to see him. He was 55, after all—very old in the eyes of a 14-year-old—and I had no way of knowing if this was going to be my final chance to see the man on stage.

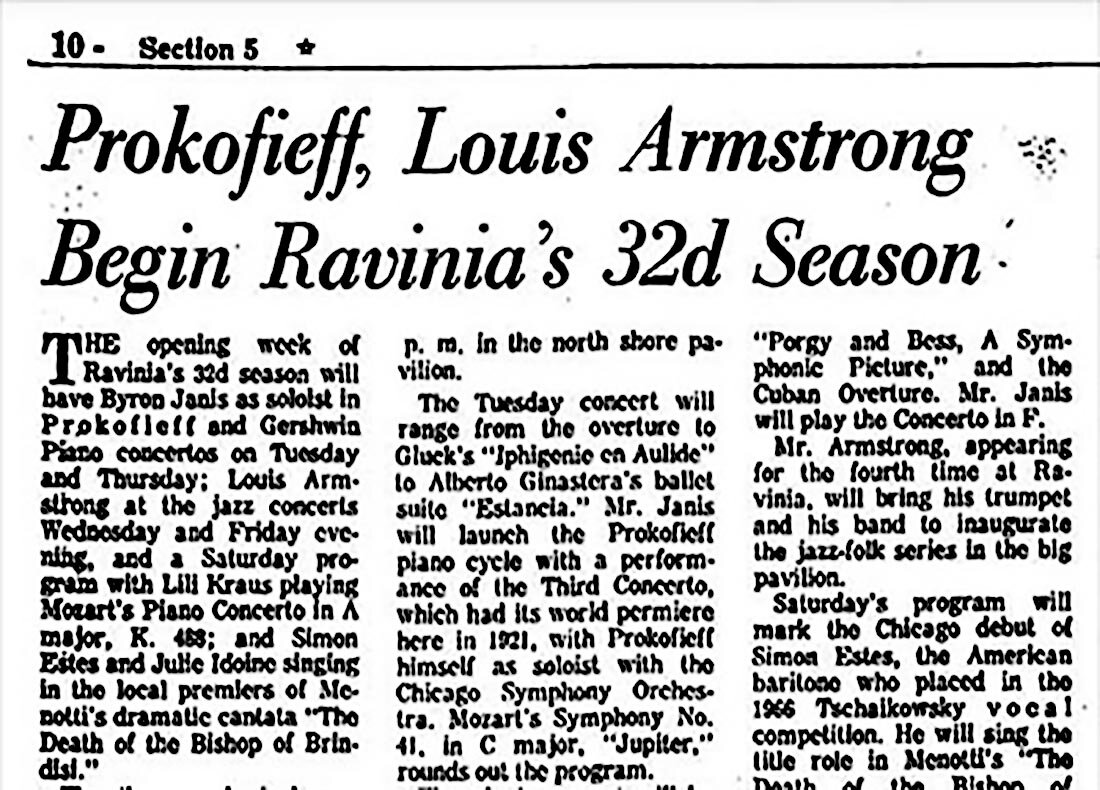

Chicago Tribune Article July 17, 1956

Armstrong was the first great international star I ever saw in person. The press coverage of his Ravinia debut not only endorsed my choice, but befitted a larger occasion as well. Jazz was still very new to Ravinia then, and it still seemed utterly contradictory to mention the two words in the same sentence. When Benny Goodman had appeared at Ravinia in August 1938, fresh from his triumph at Carnegie Hall earlier that year, the young crowds seemed to frighten the park management, even as the dollars they brought in wiped away an entire season’s deficit in two hours. But it would be 17 years before jazz would be invited back to Ravinia. On July 11, 1955, in what was called “an off-night experiment,” the “cool” chamber jazz of the Dave Brubeck Quartet drew about 4,000. The concert was peaceful, appropriately intellectual, and thoroughly compatible with what was considered the comportment of a Ravinia evening. And the box office numbers were similarly well-met. The next year Brubeck was back.

But Louis Armstrong was neither cool nor intellectual. His presence was a step into the unknown for Ravinia—a slice of hot and brash Americana elbowing its way into this cultural sanctuary. This was why the press turned out in such force that night. Reporters enjoyed dwelling on the stark populist contrasts of jazz at Ravinia because they inferred issues of what news outlets might today call “class warfare.” A page of photos in the Chicago American was headlined “Satchmo’s Heat Rocks Ravinia.” Newsmen wrote about “hot music” at “snooty” Ravinia, how “Armstrong brought down the staid walls of convention,” and so on. Armstrong was Ravinia’s Spartacus. The early years of the Newport Jazz Festival were at that time being driven by precisely the same clash of “high” and “low” sensibilities. Armstrong himself added a more than a touch of that dynamic with his appearance in the hit movie High Society, which was set in Newport and still in theaters when he arrived at Ravinia in 1956.

Armstrong performed two concerts at Ravinia that week, Monday the 16th and Wednesday the 18th; I attended the second performance, which was just as well. Monday was wet and rainy, but even if weather held down attendance, it didn’t stop Armstrong from reportedly drawing a park-record 6,300 that night.

Page excerpt from Ravinia's 1956 Program Book

But that was nothing compared to Wednesday. It was good that I got an early start that evening; a monster traffic jam was gathering along the Green Bay and Sheridan Road approaches by 7:30, and for the first time that anyone could remember, the main parking lot ran completely out of space half an hour before the 8:30 show. Parked cars began backing up on Lake Cook Road as far west as the Edens Expressway. A total of 12,000 people would fill Ravinia that night.

Then as now, there was merchandise for sale in the park. You could pick up all the current Armstrong LPs that night, including Ambassador Satch, Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy, and the soundtrack album to High Society. In those days, a staple of any Armstrong concert was also the souvenir booklet, a glossy, 24-page album of articles and pictures. My dad financed the $1 for a copy. Three years later I was lucky enough to get Armstrong to sign it. (I wonder what it’s worth now …)

Armstrong took the stage and began playing “Sleepy Time Down South” around 8:35. I know now it was the same concert he was giving just about anywhere in those days, with the same solos, same jokes, and same hokum—such as trombonist Trummy Young playing “Margie” while working the slide with his foot or Dale Jones playing his bass while lying on his back—but to a 14-year-old it was all a revelation to behold.

Armstrong performs with singer Velma Middleton in 1956

After about an hour, singer Velma Middleton came out—all 300 pounds of her. Her weight was an asset she exploited even more than her singing, especially when she would jump up and down (clearing maybe an inch between herself and the ground), then drop to the stage in a climactic split. Jazz critics hated her, but Armstrong was loyal. (She died in 1961 at age 43, on the road with the band in Sierra Leone.)

In 1956 Armstrong was the personification of the heart and soul of jazz around the world—as he perhaps still is today, at some level. But his music had become by then more a representation of jazz then a living, organic example of it. Younger people were turning to Brubeck and Miles Davis, while Ellington, Basie, and Goodman were still seen as relatively contemporary. Armstrong was in a way a ghost of jazz antiquity, the one surviving star of its origins in New Orleans. He had become to jazz what Roy Rogers was to Westerns; one performance of “(Back Home Again in) Indiana” had no need to distinguish itself from another. This was perhaps also a kind of quality-control strategy, eliminating any pressure to constantly create while at the same time guaranteeing to every audience that it would hear the Louis Armstrong it expected. Yet, it was still a real experience. The notes, ideas, and design of the material may have become settled, but the unique sound of his horn—the passion of its violent vibrato and his dramatic instinct for emotional pacing—was still intact and could not hide behind the institutionalized solos and ensembles.

After Armstrong left the stage that Wednesday and the 12,000 fans flooded back onto Sheridan and Green Bay Roads or the trains that waited outside the gates, Ravinia became a kind of Brigadoon. Calmness, quiet, and order returned as Georg Solti (who was among the 12,000 that Wednesday), Jacob Lateiner, Aaron Copland, and Claude Rains filled out the week. But it wasn’t over. Armstrong would be back.

Chicago Tribune Article June 25 1967

Four years later, I’d managed to graduate from New Trier High School. My prize now vastly overvalued my accomplishment, not just two tickets to each of Armstrong’s Ravinia concerts, July 20 and 22, but second-row, center tickets that put me no more than 25 feet from the bell of his horn. This was lucky because I had also recently acquired a new gadget from Grundig that was something of a miracle—a battery-operated reel-to-reel tape recorder, small enough to carry into any concert and let you carry out the music. The sound was tinny and antique, but better than a mere memory. Such machines were so rare then that there were no admonitions in the Ravinia program boilerplate against recording. I took a friend to each of the concerts, but I can’t imagine what a jerk they must have thought I was, because I paid far more attention to my recorder than to them.

Armstrong could occasionally surprise an audience with an unexpected treat. It may have been the presence of pianist Lil Hardin, a Chicago resident and Armstrong’s second wife, or maybe it was just a whim, but four or five songs into the second half of the Wednesday concert, as the applause for “Ole Miss Blues” was dying away, he put his horn to his lips and fired off a flawless run through the most famous single cadenza in the history of jazz: the call to arms of “West End Blues.” I could hardly believe my ears. It was like hearing Gershwin himself rip through Rhapsody in Blue or Rachmaninoff tear off the opening to his Second Piano Concerto. Armstrong’s landmark 1928 recording was imagined as a stunning virtuoso set piece, and that night it was all that and more; simple 12-bar blues performed with the force and spirit of an aria. He held the famously long high note in a single breath over four slow bars. His vibrato radiated a furious heat as he climbed toward the final climactic stab, then the retreat into the darker denouement of the coda. Barely a note had been altered since 1928. But this was jazz at its most spectacular and demanding. I have never heard a trumpet sound the same since. Oscar Peterson was absolutely right, Armstrong was a “fantastic” trumpet player, and in 1960 it was not yet too late to experience.

He played another song that night that had taken up brief residence in his repertoire, somehow never got recorded, and was soon gone. His most recent film, The Five Pennies with Danny Kaye, was a biopic of ’20s trumpeter Red Nichols and featured the old standard, “Bill Bailey Won’t You Please Come Home.” The version he played at Ravinia owed little to the movie version, but it was a punishing run through the upper trumpet register that Armstrong navigated like a master. I’ve never heard another version for comparison. Performances seem to have been rare to non-existent.

When Armstrong came back to Ravinia on June 24 and 26, 1964, the only song anyone wanted to hear (except the critics, who had already heard it too much) was “Hello Dolly.” The song had reinvented Armstrong’s career and was bringing him the largest audiences of his career. But it was an audience that was more interested in hearing him sing than play. The world was beginning to forget the cornerstone on which his reputation had been built. For Armstrong, who was about to turn 63 on August 4, this probably suited him. With no wish to retire, he figured, this could only help extend his career. His next big sellers, “Cabaret” and “It’s a Wonderful World” contained no trumpet solos at all.

1964 Interview with Armstrong at Ravinia

As a young man Armstrong had largely invented his own performance techniques, which were intuitive, sometimes unorthodox, and, in the formal sense perhaps, thoroughly incorrect. But they endowed him with a sound so unique that trumpet players today trained without such “bad habits” find it almost impossible to reverse-engineer his astonishing timbre and accurately reproduce it. But for all its distinctiveness, it was not necessarily built to stand against challenges of age. By 1964 Armstrong was accommodating his weakening trumpet powers by compressing some of his set pieces like with “Royal Garden Blues,” often shortening or eliminating solo routines and letting sideman pick up the slack.

Lil Hardin was in the audience again for the opening-week concerts of Ravinia’s 32nd season and what would be Armstrong’s final stand at the festival on June 28 and 30, 1967. He introduced her from the stage before playing “Cabaret.” I had recently acquired an 8mm movie camera and brought that along with my latest portable tape recorder. Ushers were starting to look for such devices now, so I had to be more discreet in my misbehavior. On the other hand, there was less to record by then. Armstrong didn’t even take a solo in his traditional warm-up opener, “Indiana,” and his timing and punch seemed off more than once. Increasingly, the trumpet was becoming a prop in support of Louis Armstrong, the singer, the persona. The Chicago Tribune didn’t bother to review either concert, and there would be no surprises this time.

A little over a year later, in September 1968, Armstrong entered Beth Israel Hospital in New York for what would become a series of hospitalizations that would make his public appearances less and less frequent. Each one acquired the aura of a farewell as his congestive heart failure made him appear increasingly gaunt. But anyone who had seen the great Satchmo at Ravinia in 1956 or 1960 would never need to ask whether he was once a good trumpet player. He was fantastic.

A contributor to DownBeat and National Public Radio, John McDonough teaches jazz history at Northwestern University.