It Ain’t Necessarily So

By Mark Thomas Ketterson

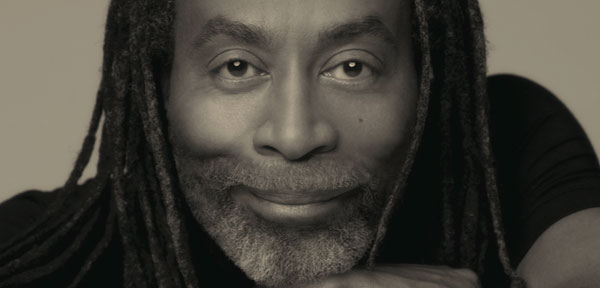

Some years ago I was browsing through bins of CDs at a music superstore and one album virtually jumped off the rack and yelled, “Buy me!” The album was

entitled Hush, and pictured on the cover were two smiling gentlemen I admired very much: cellist Yo-Yo Ma and the inimitable, multiple Grammy

Award–winning singer and conductor Bobby McFerrin.

It was a happy photo, and a very happy CD. The title cut was a delightful rendition of “Hush Little

Baby” that had me bobbing my head the whole drive home. Ma did wonderful things, and McFerrin, who returns to Ravinia on July 8 to conduct the hits from

Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, revealed himself to be an amazing one-man band as he provided percussion, counterpoint and, of course, the vocals—all

in that unique voice of his. His sound, with its bits of pop, funk and dashes of other things, was impossible to classify, almost as if McFerrin embodied

the muse of music itself.

Some years ago I was browsing through bins of CDs at a music superstore and one album virtually jumped off the rack and yelled, “Buy me!” The album was

entitled Hush, and pictured on the cover were two smiling gentlemen I admired very much: cellist Yo-Yo Ma and the inimitable, multiple Grammy

Award–winning singer and conductor Bobby McFerrin.

It was a happy photo, and a very happy CD. The title cut was a delightful rendition of “Hush Little

Baby” that had me bobbing my head the whole drive home. Ma did wonderful things, and McFerrin, who returns to Ravinia on July 8 to conduct the hits from

Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, revealed himself to be an amazing one-man band as he provided percussion, counterpoint and, of course, the vocals—all

in that unique voice of his. His sound, with its bits of pop, funk and dashes of other things, was impossible to classify, almost as if McFerrin embodied

the muse of music itself.

That musical spirit was likely inborn: McFerrin is the son of singer Sara Copper and the great Robert McFerrin, who is well remembered as the first

African-American man to sing at the Metropolitan Opera. McFerrin Sr. bowed at the Met in 1955, three weeks after contralto Marian Anderson broke the color

barrier for Met singers with her historic performance in Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera. Opera buffs tend towards diva obsession, so the parade of

female singers who graced the company in the wake of Anderson’s success has tended to eclipse the contributions of the gentlemen (not to mention that of

ballerina Janet Collins, who was actually the first black artist at the Met). McFerrin Sr. had already distinguished himself on Broadway and at the New

York City Opera with a glorious, ringing baritone that made him an ideal interpreter of Verdi. He was to remain for several years at the Met, where his

assignments included Amonasro in Aida (the vehicle of his debut) as well as the title role of Rigoletto and Valentin in Gounod’s Faust. His milieu was music; quite a heady environment for his son Robert Jr. (who we all know as “Bobby”) and his daughter Brenda. “I grew up in

a house full of music,” Bobby McFerrin recalls. “All kinds of music. I can’t begin to tell you how grateful I am for that. I have lots of specific

memories: all of us singing together, hiding under the piano listening to my father teach and practice, going to church with my mother to sing in the

choir, ‘conducting’ our stereo as it played Beethoven, my mom putting on music to make me feel better when I was sick. I know all those experiences shaped

me as a musician and as a person.”

That musical spirit was likely inborn: McFerrin is the son of singer Sara Copper and the great Robert McFerrin, who is well remembered as the first

African-American man to sing at the Metropolitan Opera. McFerrin Sr. bowed at the Met in 1955, three weeks after contralto Marian Anderson broke the color

barrier for Met singers with her historic performance in Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera. Opera buffs tend towards diva obsession, so the parade of

female singers who graced the company in the wake of Anderson’s success has tended to eclipse the contributions of the gentlemen (not to mention that of

ballerina Janet Collins, who was actually the first black artist at the Met). McFerrin Sr. had already distinguished himself on Broadway and at the New

York City Opera with a glorious, ringing baritone that made him an ideal interpreter of Verdi. He was to remain for several years at the Met, where his

assignments included Amonasro in Aida (the vehicle of his debut) as well as the title role of Rigoletto and Valentin in Gounod’s Faust. His milieu was music; quite a heady environment for his son Robert Jr. (who we all know as “Bobby”) and his daughter Brenda. “I grew up in

a house full of music,” Bobby McFerrin recalls. “All kinds of music. I can’t begin to tell you how grateful I am for that. I have lots of specific

memories: all of us singing together, hiding under the piano listening to my father teach and practice, going to church with my mother to sing in the

choir, ‘conducting’ our stereo as it played Beethoven, my mom putting on music to make me feel better when I was sick. I know all those experiences shaped

me as a musician and as a person.”

Although we tend to associate Bobby McFerrin as a vocalist, he began his formal musical training on the clarinet, later turning to piano. “I never imagined I’d be anything but a musician,” he explains. “I thought I’d be different from everyone else in the family by becoming an instrumentalist instead of a vocalist.” Vocal influences in this household were inescapable, however, and McFerrin soon found himself studying voice “by osmosis.” “I listened to my father practice and teach. He was very hard on his students, and even harder on himself; he held a very high standard for music making. I can’t imagine a better formal education. But I also just spent a lot of time alone in a room, singing and singing, learning to make the sounds I could hear in my head. I can think of many moments when influences really hit hard: watching the movie Zulu with Michael Caine, there was a scene with African music and dance; listening to Sly Stone; hearing Herbie Hancock with the Mwandishi band—too many to count. And I know that working for so many years as a pianist—I started working at 14 and didn’t realize I was a singer until I was 27—had a lot of effect on the way I hear things. I like to map out the bass line and the harmony and the melody. But honestly, the osmosis effect was still the key; I think everything we hear shapes how we hear the next thing.”

In 1958 McFerrin Sr. scored an assignment that would have a profound impact on his son: he was hired to dub the singing for Sidney Poitier in Otto Preminger’s film rendition of George Gershwin’s classic folk opera Porgy and Bess , based on the play of the same name byDuBose and Dorothy Heyward (as well as DuBose’s original novel, Porgy , from which the play was adapted).

“When my father got the job singing the part of Porgy, everything changed for my family and for me. The memories are all mixed up together: moving to Los Angeles, going to the beach, listening to dad sing the songs, seeing the palm trees, getting to meet Sammy Davis Jr., watching the choir rehearse under Ken Darby. Then the album came out and we played it over and over again. The music became the background music for our lives for a good long while.”

The score has become essential for McFerrin as an adult as well. Since the 1990s he has won great acclaim with a concert version that has graced various musical centers, including Ravinia in 1997. “I got to meet André Previn, too,” he remembers. “When I first conducted the piece, I called him. I wished I could have used the overture he wrote for the film.” McFerrin categorically denies reports that he sought to rescue the score from classical musicians who lost its jazz elements, however. “I really don’t think I’ve ever said that. On the contrary, sometimes it’s hard for orchestra musicians to swing, but I’ve conducted this score many times and I don’t remember a single time it was a problem. The swing is written into the score. He [Gershwin] knew exactly what he wanted.”

The influence of Porgy and Bess on the music world is inestimable. The opera premiered in 1935 at the Alvin Theatre on Broadway (a proper unveiling in an opera house for a work cast with black singers was deemed unthinkable in those less enlightened times), where it ran for an impressive 124 performances. A toehold in the operatic repertory took some time to achieve, at least in the United States. Paradoxically, given that the piece is now regarded as the Great American Opera, America was a bit late to her own party. Porgy and Bess enjoyed operatic currency in Europe before becoming fully established at home, sometimes performed by Caucasian performers in blackface (a practice the Gershwin estate soon clamped down on). A celebrated mounting at Houston Grand Opera in 1976 led to a much-needed re-evaluation, and Porgy and Bess finally entered the repertory of the Metropolitan Opera in 1985. Lyric Opera of Chicago has twice enjoyed tremendous success with the piece, first in 2008 and again in 2014. In the meantime, Porgy and Bess has seen innumerable reinterpretations in every conceivable musical genre from pop to rock to jazz— it’s estimated that “Summertime,” the score’s biggest hit tune, has been covered by over 33,000 artists.

With that popularity has come controversy, particularly in this post–civil rights era, when the depiction of southern blacks in Porgy and Bess has been seen by some as patronizing and demeaning, despite the ineffably beautiful music. Rumors circulated about one Met baritone who declined to sing “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” as written, preferring to substitute the grammatically correct “are.” Composer Ned Rorem, when commissioned for an operatic adaptation of another Heyward novel, Mamba’s Daughters , withdrew from the project, stating, “How could a white artist, however compassionate, presume to depict a black nightmare from the inside out?”

“As we look back at it now, it seems dated and stereotypical,” McFerrin admits. “But I think Gershwin was making a sincere effort to tell the truth. He did his homework, he visited churches and neighborhoods, and I can tell he was sincerely, personally drawn to the sounds and tried to follow the music and let it lead. The question of dialect and pronunciation comes up around the spirituals, too. I have such incredible memories of my dad in our living room working on the spirituals with the legendary [composer/arranger] Hall Johnson. He coached both Marian Anderson and my dad in singing that material and spearheaded a lot of the efforts to bring those songs into the concert halls. His grandmother was a slave, and he had very specific ideas about the ‘right’ way to pronounce the lyrics. And maybe those ways sound contrived or politically incorrect now, but for him that was the true sound of it. If I thought there was real racism in the piece, I’d talk to the audience about it when I perform it. It is fascinating how the piece has functioned in the freelance economy. It’s needed the casting of a lot of wonderful African-American singers, and I think that’s good. I’m glad they are working.”

They certainly are. A glance at the resumés of some of the most internationally celebrated singers of the last several decades, from Leontyne Price and William Warfield, to Grace Bumbry and Simon Estes, as well as Adina Aaron and Eric Owens, reveals an association with Porgy and Bess. Even Maya Angelou once took part in an international tour of the work. Ravinia’s audience will have the opportunity to savor McFerrin’s take on Gershwin’s masterpiece with singers including Broadway’s Brian Stokes Mitchell and the delectable soprano Nicole Cabell. He’s also enlisted Josephine Lee—with whom he’s worked on his last two Ravinia appearances, including the 2003 gala with Kathleen Battle and Denyce Graves—to assemble and prepare the chorus.

Before wrapping up, I cannot resist telling McFerrin how much he cheered me up with that Hush Little Baby collaboration with Yo-Yo Ma. “Collaborations are a joy,” he enthuses, “and I’ve had some great ones: Yo-Yo, Chick Corea, the Yellowjackets, Voicestra, the Spirityouall band. All different, all wonderful.

“I think my job as an artist is to bring joy. That’s it. When I’m on stage I try to invite the audience into the incredible feeling of joy and freedom I get when I sing, when I follow the music forward. I want the audience to leave the theater feeling better than they felt when they came in. I want to remind us all of what a joy it is to be alive, to dance and sing, to make music together.”

Mark Thomas Ketterson is the Chicago correspondent for Opera News . He has also written for Playbill , Chicago magazine, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Houston Grand Opera, Washington National Opera, and the Kennedy Center.

(Original article appeared in Ravinia Magazine. For the complete magazine, click here.)