Confessions of a Former Music Snob

By John Schauer

If you’ve read any of my previous blogs, it should be apparent that as a child, I was the ultimate classical music nerd. I had no interest in the pop music my classmates were listening to, at least not until the “British invasion” of the early 1960s (Petula Clark’s “Downtown” was the turning point for me). But I especially disdained country/western music.

This is not something I was taught at home; my parents would regularly enjoy the country stylings of Joe Shott and the Hot Shots on local-access television while I cringed, and even after I became an aficionado of ’60s rock, I was mortified that they had moved on to the low-brow antics of the CBS variety series Hee Haw. In general, I feared that television was destroying our culture as more and more series like The Beverly Hillbillies, Petticoat Junction, Gomer Pyle USMC, Mayberry RFD, and others celebrated the rural southern lifestyle.

Country music seemed too simplistic to be worth listening to, but I was later to discover how marvelous it is for dancing. I can trace that interest back to the glorious black-and-white 1930s musicals of Busby Berkeley. I found the mass production numbers to be absolutely mesmerizing (the best of all perhaps is the “Lullaby of Broadway” segment from Gold Diggers of 1935), and I longed to be part of a massed group of synchronized dancers moving in perfect precision. It was what drew me to “The Hustle” in 1975, even as my friends disparaged it as an instrument of conformity. But as we all know, disco died, and my synchronized dancing days seemed to be over.

That is, until the early 1990s, when country/western line dancing became a national craze. I lived only a few miles from a western bar that offered dance lessons, and I attended several times a week. Within a few months, I had mastered 28 different line dances. I also took lessons in two-step, country waltz, and country swing. The result was that I was regularly being exposed to the country music of the time and growing to love it. I decided to actually purchase a country album or two. But where to start?

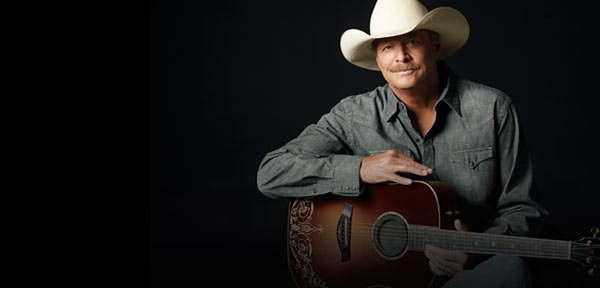

I saw a TV show featuring the top 10 country videos at the time and was struck by “Here in the Real World” by Alan Jackson. Unlike other country artists, he didn’t make a great display of being a caricature of a boisterous, s**t-kicking redneck bumpkin. In the context of many other country artists, he stood out as practically aristocratic, a true country gentleman, even if he wrote songs with titles like “Blue Blooded Woman (and a Redneck Man).” There was a genuine sincerity to everything he sang that was irresistible. I ran out and bought his first couple of albums. Today I laugh to recall that at first, I actually turned the volume down on my stereo when listening to them, I was so afraid people in the adjacent apartments, whom I barely knew, might hear me actually listening to country music.

I soon lost that reticence. In fact, after one of my colleagues at San Francisco Opera, where I worked at the time, jokingly suggested I bore a resemblance to Jackson (I didn’t really, other than having a mustache and blondish hair), I collaborated with a couple of them to create a photographic homage. The head of the wig and makeup department took me to a professional wig supplier—where I bought what looked like a huge Farrah Fawcett wig, which he then cut and styled from photos—and one of the company photographers did a sitting with me in my full line-dance country drag. I used it as my Christmas card that year.

By this time Alan Jackson was winning every country music award there was. The only exception came during a brief period when it was announced that he was going to separate from his childhood-sweetheart wife, and the Nashville establishment seemed to turn its back on him—an amazing reaction from an industry that for decades celebrated breakups and divorce. His album that came out around that time, Everything I Love, remains my favorite, a dazzling showcase of different country music styles, even incorporating Dixieland, but it was virtually snubbed by the major awards shows. Fortunately he returned to favor after reconciling with his wife, but I still consider Everything I Love to be his masterpiece.

Another quality of his music that won me over was that he stayed true to traditional country. His backup band, The Strayhorns, was a classic country ensemble of fiddle, electric guitar, steel guitar, keyboards, bass guitar, and drums who played with tight-knit cohesion and suave musicianship. The early ’90s had also seen the emergence of the “New Country,” artists like Faith Hill and Shania Twain and others who, to my ears, were not so much country as soft rock, and a lot of country artists started softening their style in an attempt to win a crossover audience.

Not Alan. He kept it country. He kept it authentic. And he kept it sincere. You can sample that sincerity when he makes his Ravinia debut on August 31.