By John Schauer

Living my formative years during the ’60s, my immersion into popular music came around the time of what came to be known as “protest songs.” Where earlier rock and pop songs were mainly concerned with teenage romance and all the problems associated with it—rejection, parental disapproval, rivals in love—pop artists started addressing serious social concerns, such as civil rights and the developing war in Vietnam. It was also the era of “folk-rock” and the ascendance of the singer-songwriter. Pop artists no longer simply went into the studio to record a piece of music handed to them by their agent or record company executive. The idea grew that someone singing their own music had a greater artistic integrity—who could better interpret their poetry and melodic flights of fancy than the writer him- or herself? “Cover” versions of the more popular songs were often what put a song in the top 10—The Fifth Dimension singing Laura Nyro’s “Wedding Bell Blues,” or the gorgeous arrangement Joshua Rifkin made of Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now” for Judy Collins—but to extract the full measure of meaning from a song, I and many others preferred to turn to the original source.

Living my formative years during the ’60s, my immersion into popular music came around the time of what came to be known as “protest songs.” Where earlier rock and pop songs were mainly concerned with teenage romance and all the problems associated with it—rejection, parental disapproval, rivals in love—pop artists started addressing serious social concerns, such as civil rights and the developing war in Vietnam. It was also the era of “folk-rock” and the ascendance of the singer-songwriter. Pop artists no longer simply went into the studio to record a piece of music handed to them by their agent or record company executive. The idea grew that someone singing their own music had a greater artistic integrity—who could better interpret their poetry and melodic flights of fancy than the writer him- or herself? “Cover” versions of the more popular songs were often what put a song in the top 10—The Fifth Dimension singing Laura Nyro’s “Wedding Bell Blues,” or the gorgeous arrangement Joshua Rifkin made of Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now” for Judy Collins—but to extract the full measure of meaning from a song, I and many others preferred to turn to the original source.

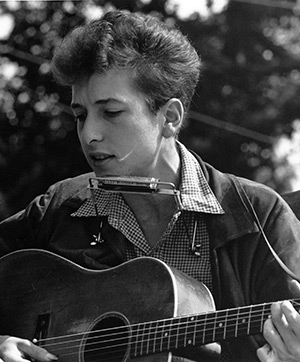

But I drew the line at Bob Dylan. I first got to know his songs through the hit recordings of Joan Baez, The Byrds, or Peter, Paul and Mary; even Cher launched her solo career with a number-one hit cover of “All I Really Want to Do,” and her debut album included two additional Dylan tunes. So when I finally sampled Dylan’s own renditions, I was horrified. Here, I felt, was one instance where other performers could do a much better job of conveying the composer’s inspiration than he himself could. Just as I always had a natural resistance to Maria Callas’s opera recordings because I found her sound insurmountably unpleasant, I simply couldn’t get past Dylan’s voice.

My attitude changed during my years in graduate school, when I had a roommate who was perhaps the most fanatic Dylan aficionado I’ve ever met. He not only embraced but rejoiced in a vocal technique that, he pointed out, had once been described by one critic as sounding like “a hound dog caught in barbed wire.” I didn’t find the description very enticing, but I had little choice in the matter. It seemed that no matter what topic of conversation we had during frequent late-night “rap sessions” (in those days, rapping meant simply talking, not the modern relative of hip-hop music, which had not yet been concocted), inevitably my roommate would suddenly say, “You know, Bob Dylan wrote a song about precisely that,” and would then—often over my objections—force me to listen to Dylan’s musical commentary. And more often than not, one song would lead him to subject me to another, and another.

My attitude changed during my years in graduate school, when I had a roommate who was perhaps the most fanatic Dylan aficionado I’ve ever met. He not only embraced but rejoiced in a vocal technique that, he pointed out, had once been described by one critic as sounding like “a hound dog caught in barbed wire.” I didn’t find the description very enticing, but I had little choice in the matter. It seemed that no matter what topic of conversation we had during frequent late-night “rap sessions” (in those days, rapping meant simply talking, not the modern relative of hip-hop music, which had not yet been concocted), inevitably my roommate would suddenly say, “You know, Bob Dylan wrote a song about precisely that,” and would then—often over my objections—force me to listen to Dylan’s musical commentary. And more often than not, one song would lead him to subject me to another, and another.

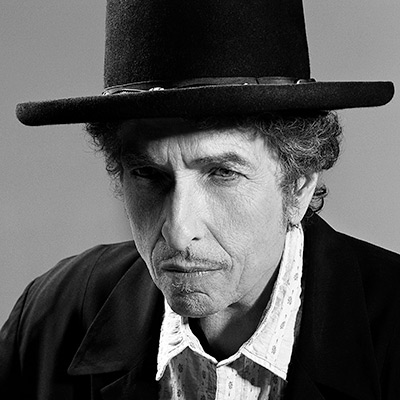

At first my roomie’s method had the opposite effect of what he intended, and I came to dread being exposed to yet another Dylan opus. But gradually it dawned on me that he was right—that Dylan did have something to say about just about everything. And with a musical career many times longer than most pop artists flourished, Dylan had ample opportunity to expound on myriad subjects. Musically, too, he adapted and changed over the years. I still remember the furor that erupted when he violated the “purity” of the acoustic sound championed by most singer-songwriters and had the audacity to use electric guitars at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, and he again raised eyebrows when he exhibited a strong country/western influence on his John Wesley Harding album. Since then, however, I don’t think anyone has been too surprised by anything Dylan has done; we’ve come to expect the new or unusual as he continues to chronicle our zeitgeist as perhaps no other pop artist has. If anyone has earned the right to the adjective “iconic,” it is Bob Dylan.

Tickets for the June 24 performance of Bob Dylan and his band with Mavis Staples can be purchased at Ravinia.org