In 1896, Morris Gershovitz and his wife, Rose, were living above a pawnshop on New York’s Lower East Side. In December of that year, the immigrant couple saw the birth of their first child, a son, whom they named Israel. In September of 1898, the Gershovitzes, now in Brooklyn, welcomed their second son, Jacob. Within a few weeks the family moved back to Manhattan, where they occupied a second-floor flat above a phonograph shop.

They’d move many more times. Morris Gershovitz was forever trying his hand at a new business, and he insisted on living close to his workplace. The Gershovitzes had two more children, Arthur and Frances, and eventually the family name was Americanized. The two oldest boys, Israel and Jacob, would be known to the world as Ira and George Gershwin. Within not too many years, the Gershwin brothers would elevate American popular song to an art form, collaborate on numerous Broadway musicals and revues, and create a landmark American opera.

Unlike his brother George, young Ira was quiet and detached, an introvert. He was the family intellectual, a good student in school, and although he’d spent much of his youth absorbing the cheap adventure novels of the time, by the age of 10, he’d read Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet three times.

For high school, Ira attended Townsend Harris Hall, a school for exceptional students. Ira loved words, and while he pored over all types of prose and poetry, what particularly captivated him was light verse. He bought poetry anthologies with his 40-cents-a-week allowance and collected over 200 volumes of Lewis Carroll, James Russell Lowell, and even Shakespeare. He read poems that spanned the entire literary tradition, and sometime in his early years, he discovered the wealth of the New York Public Library. The first book he checked out was a volume of Thackery, who also wrote a good deal of light verse:

Spitting is a nasty thing

Which French people do.

Little Lording, don’t begin

Expectorating too.

Ira, though, didn’t need Thackery or the New York Public Library for inspiration. During his boyhood, rhyming poetry was everywhere, with all the New York dailies offering columns of light verse. The most famous of them was the New York World’s “The Conning Tower,” authored by Franklin Pierce Adams or F.P.A. as he was known to his adoring followers. He was a favorite of the young Ira, who compiled scrapbooks of his writings.

Ira, though, didn’t need Thackery or the New York Public Library for inspiration. During his boyhood, rhyming poetry was everywhere, with all the New York dailies offering columns of light verse. The most famous of them was the New York World’s “The Conning Tower,” authored by Franklin Pierce Adams or F.P.A. as he was known to his adoring followers. He was a favorite of the young Ira, who compiled scrapbooks of his writings.

Our dining-room is pretty dark;

Our kitchen’s hot and very small;

The “view” we get of Central Park

We really do not get at all.

(from F.P.A.’s poem “The Flat-Hunter’s Way”)

Ira’s close high-school friend was Yip (E.Y.) Harburg, who would later write lyrics for such classics as “April in Paris,” “It’s Only a Paper Moon,” and all the songs from The Wizard of Oz. He also wrote the words to The Great Depression anthem “Brother Can You Spare a Dime?”

To stave off the boredom Ira and Yip experienced in algebra class, the two versifiers started their own “column,” dubbed “The Daily Pass-It.” They printed poems and cartoons on toilet paper and circulated them among their fellow students. Eventually, a column in the school paper came their way: “Much Ado,” as they called it, satirized teachers and students in quatrains. Ira and Yip then went to the City College of New York and published a column “Gargoyle Gargles” in the college newspaper. “We were living in a time of literate revelry in the New York daily press,” Harburg explained in the book Reminiscences by Jewish Intellectuals of New York. “F.P.A., Russel Crouse, Don Marquis, Alexander Woollcott, Dorothy Parker, Bob Benchley. We wanted to be part of it.”

Young George Gershwin became fluent in the sounds of America by simply living in a city that was full of those sounds, a hearty stew of jazz, klezmer, and the music of half a dozen European countries. His brother Ira was no different, except he dealt in words. In the beginning, Ira strove constantly to fit the spoken American language into fixed poetic rhythm. Above all else, light verse must sound light and appear to come from the poet’s pen without effort, but Ira’s early poems were filled with awkward inversions where he did his best to avoid the clash between meter and language.

Young George Gershwin became fluent in the sounds of America by simply living in a city that was full of those sounds, a hearty stew of jazz, klezmer, and the music of half a dozen European countries. His brother Ira was no different, except he dealt in words. In the beginning, Ira strove constantly to fit the spoken American language into fixed poetic rhythm. Above all else, light verse must sound light and appear to come from the poet’s pen without effort, but Ira’s early poems were filled with awkward inversions where he did his best to avoid the clash between meter and language.

For Ira, the ease and lightness, the sound of effortless creation, came when he turned from poetry to song. Following the musical notes and melodic contours gave his words an ease and naturalness that they lacked when he tried to conform to a regular poetic meter. He now could play with the short and long syllables of American speech. “Lyrics,” he frequently pointed out, “should sound like rhymed conversation.”

Ira had admired W.S. Gilbert as a light-verse poet. He’d read plenty of Gilbert creations in the many anthologies he’d collected as a youngster. One day, Ira’s father showed up with an armful of phonograph records, the complete Gilbert and Sullivan H.M.S. Pinafore. Ira had read many of the verses in his anthologies and was disappointed that “practically all of the lyrics were written first.”

In 1925, Ira told the New York Tribune, “It all comes down to this: in the old days, they would write their lyrics first and then get musical settings, whereas today the worry of songwriters is the melody of the song. The song is the important thing, the combination of words and music, rather than the words and music as separate entities. The reason that some of our songwriters are unsuccessful is that they regard the lyrics the same way Gilbert did, they don’t strive for union of the composer and lyricist. They are not willing to sacrifice themselves to the demands or limitation of the tune, the movement, and syncopation.”

On the afternoon of Tuesday, February 12, 1924 (Lincoln’s birthday), bandleader Paul Whiteman offered something called “An Experiment in Modern Music” in New York’s Aeolian Hall. It was a hodge-podge of various pieces; among them was a piece by 25-year-old George Gershwin.

George had learned of the concert and his involvement in it only five weeks before. Busy with other projects, he had little time to produce a full-scale work, but he settled on a piece for piano and orchestra. He began composing on Monday, January 7. At the urging of brother Ira, he changed the title. Ira had spent an afternoon at a gallery admiring the paintings of James McNeill Whistler. He loved the artist’s descriptive titles: Arrangement in Gray and Black (Whistler’s Mother). Ira suggested Rhapsody in Blue.

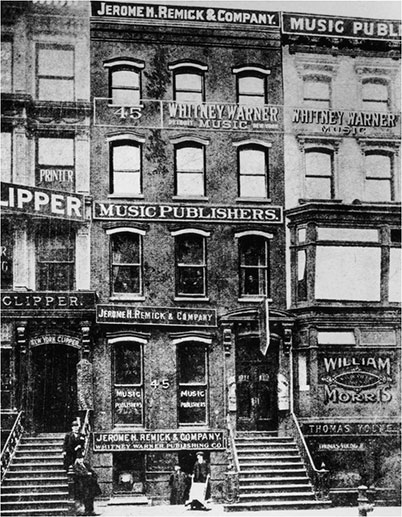

That 1924 premiere rocketed George Gershwin from a capable songwriter to a major American composer. He was only 25. He’d left high school at 15 to be a song plugger for a Tin Pan Alley music publisher. From there he worked as a rehearsal pianist and songwriter for half a dozen musical revues. While he was moving through his musical apprenticeship, his brother Ira drifted. For a time, he handed out towels in his father’s Turkish bath, and he even hit the road working for a carnival. But through all this, he wrote lyrics, eventually working with various composers on boilerplate lyrics for Pins and Needles (1922) and The Greenwich Village Follies (1923).

That 1924 premiere rocketed George Gershwin from a capable songwriter to a major American composer. He was only 25. He’d left high school at 15 to be a song plugger for a Tin Pan Alley music publisher. From there he worked as a rehearsal pianist and songwriter for half a dozen musical revues. While he was moving through his musical apprenticeship, his brother Ira drifted. For a time, he handed out towels in his father’s Turkish bath, and he even hit the road working for a carnival. But through all this, he wrote lyrics, eventually working with various composers on boilerplate lyrics for Pins and Needles (1922) and The Greenwich Village Follies (1923).

Later in 1924, the Gershwin brothers arrived at a permanent collaboration when they teamed up to write the musical Lady, Be Good!, which originally contained the Gershwins’ classic “The Man I Love”:

Someday he’ll come along

The man I love

And he’ll be big and strong

The man I love …

It was the American Century, and Gershwin songs were a large part of the accompanying soundtrack: “It Ain’t Necessarily So,” “I Got Rhythm,” “I Can’t Get Started,” “Someone to Watch Over Me,” “Love Is Here to Stay”—and that’s only a few of them. In their book The Century, Peter Jennings and Todd Brewster summed up the Gershwins’ impact on American society: “When we think about this time, it is a recording of Gershwin that we are likely to play in our mind’s ear, the soaring clarinet of Rhapsody in Blue, the romantic lyrics of ‘The Man I Love.’ ”

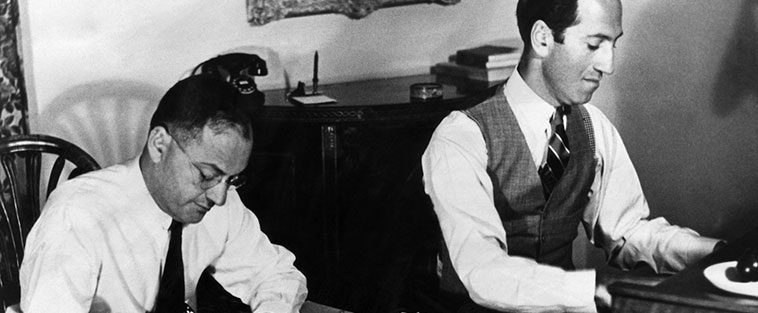

Working together, the Gershwins dominated the American musical landscape, furnishing music for 12 shows and four films. It was a unique collaboration. As Ira pointed out, “Given a fondness for music, a feeling for rhyme, a sense of whimsy and humor, an eye for the balanced sentence, an ear for the current phrase, and the ability to imagine a performer trying to put over the number in progress—given all this, I would say it takes for or five years collaborating with knowledgeable composers to become a well-rounded lyricist.” If nothing else, brother George was a knowledgeable composer and Ira was well-rounded lyricist; in fact, his fellow laborers in the vineyard of American song called Ira “The Jeweler” because of his precision in matching words and even vowel sounds to the musical line.

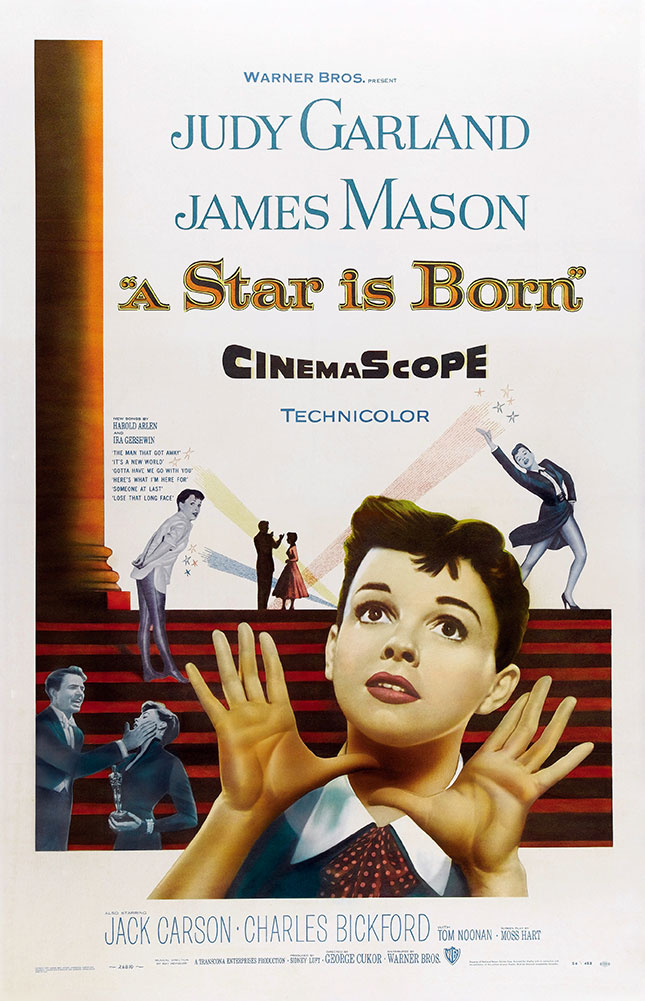

George Gershwin died of a brain tumor in 1937, and Ira, despondent, didn’t write again for three years. And when he did, he collaborated with Jerome Kern on the movie Cover Girl and with Kurt Weill on the film Where Do We Go from Here? and the musical Lady in the Dark. In 1947, Ira took 11 songs his brother had written but never used and wrote new lyrics. They were heard in film The Shocking Miss Pilgrim, starring Betty Grable. Harold Arlen and Ira wrote music for the 1954 movie A Star Is Born, and Ira later wrote lyrics for Billy Wilder’s 1964 movie Kiss Me, Stupid.

George Gershwin died of a brain tumor in 1937, and Ira, despondent, didn’t write again for three years. And when he did, he collaborated with Jerome Kern on the movie Cover Girl and with Kurt Weill on the film Where Do We Go from Here? and the musical Lady in the Dark. In 1947, Ira took 11 songs his brother had written but never used and wrote new lyrics. They were heard in film The Shocking Miss Pilgrim, starring Betty Grable. Harold Arlen and Ira wrote music for the 1954 movie A Star Is Born, and Ira later wrote lyrics for Billy Wilder’s 1964 movie Kiss Me, Stupid.

In the words of the great wordsmith, “A career in lyric writing isn’t one that anyone can muscle in on. If the lyricist who lasts isn’t a W.S. Gilbert, he is at least literate and conscientious; even when his words at times sound like something off the cuff, lots of hard work and experience have made them so.”

Ira Gershwin, the man who wrote the words for “Embraceable You” and more than 700 other songs, died quietly on August 17, 1983.

He’s still with us, though.

Jack Zimmerman is a Chicago writer who has spent his life in music.