By David Lewellen

Lara Downes thinks we have reached the right moment for unfamiliar music presented in a new way.

Downes, the founder and curator of Rising Sun Music, has spent decades finding and preserving the music of Black composers from several continents and many centuries. The pianist has been adding to her already significant discography with monthly digital releases of four or five pieces from this repertoire since February, and the first full album, New Day Begun, appeared in July. Across the recordings, she has collaborated with musicians ranging from violinist Regina Carter and violist Jordan Bak to soprano Nicole Cabell and bass-baritone Davóne Tines to the PUBLIQuartet.

Her Ravinia concert on September 7, titled “Migration and Renaissance,” will spotlight music with connections to the Great Migration, the movement by millions of African Americans from the rural South to the urban North over the course of the 20th century, and the Chicago Black Renaissance. Her collaborators for the evening—violinist Rachel Barton Pine, cellist Ifetayo Ali-Landing, and members of the Chicago Sinfonietta—are Chicago-based artists with their own history of exploring the Black repertoire.

A concert like this automatically raises thoughts about expanding the “canon” of “classical music,” but Downes would like to move beyond both of those terms. Instead of just mentally admitting Black or female composers to the canon, “we should be letting go of the perception that there is a canon,” she says.

And as for what to call the music, “genres are so fluid now, and I love working with young composers who are very free in their vision of what goes where, so I don’t know,” she adds. “Possibly we need to go back to the Duke Ellington quote about how there are only two kinds of music, good music and the other kind.”

Chicagoans Rachel Barton Pine (above) and Ifetayo Ali-Landing (right), as well as a string quartet comprising members of the diversity and inclusion–focused Chicago Sinfonietta, join Downes on the September 7 Rising Sun concert at Ravinia featuring the music of several Black composers with deep ties to the city, including groundbreakers Bonds, Price, and Nora Holt plus jazz impresario Lil Hardin Armstrong and landmark singer-songwriter Sam Cooke.

Frequently, as much in the near-present as in the past, “expanding the canon just meant more of same,” Downes says. Conductors and administrators who knew that their audiences liked Bach might program a composer from the same time period, but “there are vast differences between Bach and some contemporary who’s just okay. Listeners who love Beethoven respond to raw humanity in the music, but people don’t realize that. They think they love Beethoven because he was a ‘great composer.’ ” When a listener feels a connection to a piece of music, famous or not, “no one could have told you why you’d have that response; it’s just so emotional and authentic.”

“Plenty of music by dead white men is second-rate,” says Pine, who herself has spent decades compiling and recording the music of Black composers. She has about 450 of them in her repertory—some 150 dead and 300 living. And most classical music fans would have to work hard to name 150 composers of any race or era.

But a potential complication is that concertgoers already know and identify the first-rate music by white men. In choosing music by Black composers to perform or publish, “I’m very aware that any one piece might have to stand up for the whole cause, like the one Black partner at a law firm,” Pine says. If people hear one piece that’s mediocre, “they’ll think, ‘Oh, that’s why they haven’t been playing them for all of those years.’ ”

“I started this research not in a targeted way, but just out of curiosity,” Downes says. “Thank goodness now for the internet. When I started, it was just in libraries.” But as word of her searches spread through her professional networks and in the national media, more and more leads came in. Her first plan was to make premier recordings of 20 pieces, but “I think we passed 20 a few months ago, and the spreadsheet just keeps growing.”

One incentive to keep going, she says, was input from public radio program directors who want to diversify their lineups but don’t have recordings available. But the genre classifications of streaming services are an ongoing frustration. “Mine is classical crossover, and that’s not correct, but I have to refuse to think about that,” she says. “We’re struggling with language across the board.”

Another reason to issue recordings of unfamiliar music, Downes says, is the lack of a teaching tradition and “a hesitancy to transmit the wrong information.” She is working to release carefully curated performing editions of the music, bearing in mind that Black composers weren’t working in academic institutions and didn’t have copyists and archivists. Once she wondered to a friend how much music was still in attics, and the friend said, “A lot of those attics aren’t there anymore,” referring to neighborhoods that were destroyed for highways or “urban renewal.”

But reconstructing the right sound of this repertoire resonates with Downes. “I think I have intuitively a strong sense of this music, which is why I got into this in the first place,” she says. “That American sound and rhythmic identity feels very natural to me.”

If there is a characteristic Black sound, she says, it’s the same as what we think of as the characteristic American sound. Directly or indirectly, composers in the United States have always been influenced by spirituals, jazz, and blues—“Where in American music do we not find that?”

White American composers’ borrowings from Black music have found their way into the concert halls for a century or more, but Pine calls that synthesis rather than cultural appropriation—and it has a long tradition in Europe, too, such as the Scottish Fantasy by the German composer Max Bruch. “There’s a vast difference between caricature and what’s done respectfully,” she says. “In the classical tradition, it’s our joy and responsibility to play everyone’s music. It’s how we celebrate each other and learn from each other.”

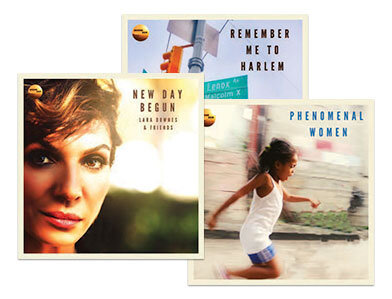

Since inaugurating Rising Sun Music in February, Lara Downes has released a series of digital EPs—including Remember Me to Harlem, with music by William Grant Still and two composers best known for their jazz, and Phenomenal Women, focused on the likes of Margaret Bonds and Florence Price—as well as the full-length New Day Begun (Downes will be signing albums after the September 7 Ravinia concert). With her foundation, Rachel Barton Pine began the Music by Black Composers project in 2001 and recently published the first of several planned volumes of sheet music to supplement instrumental training methods, including works by men and women from across four centuries and continents plus illustrated biographies of the composers, and she has added her own recordings to the repertoire’s discography.

But, Pine says, there has always been a Black American classical tradition, too, though often overlooked. And growing up in Chicago, she had more exposure to it than many of her Black contemporaries did. “Frederick Douglass and Coretta Scott King both played the violin,” she says. “This is a Black thing to do. But a lot of this repertoire has never been published, or it didn’t exist in editions suitable for children.”

When students ask her what composers they should put on their recital, she says, “Play the music you’re excited to play.” Over time and with exposure, Black composers will naturally work their way into the mix of “excited,” just as they have in Pine’s own set lists. She avoids the term “African American” because of the number of Black Caribbean and European composers in her database from the Classical and Romantic periods. Also, she points out, “No Americans of any ethnicity were writing concertos in the 1700s.”

Because she feels personal connections to so many composers, and the stories behind them, Pine admits she can’t be objective in selecting which music to publish—she abides by the vote of her foundation’s committee, composed of eminent Black musicians.

“We should let go of the perception that

there is a canon . . . go back to the Duke

Ellington quote: There are only two kinds

of music, good music and the other kind.”

While Downes and Pine have been doing their work for years, everyone was suddenly more willing to pay attention in 2020, following the videotaped murder of George Floyd and the reckoning with racism in many institutions, including classical music. “I would get calls from people saying, ‘I have a recital in five days and I need to find a piece by an African American composer,” Pine recalls. “And I would think, ‘You’ve been performing for 30 years and now it’s an emergency?’ On the other hand, better late than never. I felt there was an intransigence, a closed-mindedness, and then boom, everything changed.”

The COVID-19 pandemic, the other horror of 2020, offered opportunities for Downes to do multilayered storytelling in the virtual world. With live concert bookings picking up, “I’m really curious how it will feel to integrate both of these things,” she says. “We’re are accustomed in the concert hall to some kind of a wall. Are audiences now going into concert hall thinking about their living room where there’s no wall?” She has had good conversations with presenters, including Ravinia, about how formats might change. “Everyone really wants to hold onto the good stuff from this time,” she says. “We haven’t really figured out what to call these performances. It’s not a lecture or a recital. It’s a storytelling concert. I love sharing these stories.”

Her Ravinia concert, with the theme of migration, “honors the music by putting it in context and not saying, Look, Black composers,” she says. “I’m half Black and half Jewish, so migration and journey are at the heart of my existence.” And performing in one of the main centers of the Great Migration is “really meaningful,” she says, “because Chicago means so much in this history. It just feels emotionally resonant.” ■

David Lewellen is a Milwaukee-based journalist who writes regularly for the Chicago Symphony, Milwaukee Symphony, and other classical websites.