By Kyle MacMillan

Violin soloists sometimes add conducting to their activities, dividing their time between the two roles or combining them at times. Famous examples include Pinchas Zukerman, who has served as music director of such ensembles as the English and Saint Paul Chamber Orchestras and National Arts Centre Orchestra in Ottawa, and Joshua Bell, who holds the same post with the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields in London. In the case of Andrew Manze, a once-revered Baroque violinist, he gave up the instrument in 2009 and has devoted himself totally to conducting since, holding two posts, including chief conductor of the NDR Radiophilharmonie in Hanover.

Peter Oundjian with the other members of the Tokyo String Quartet, from the cover of their 1993 recording of Beethoven’s “late” string quartets for RCA Red Seal

What ties those instrumentalist-turned-conductors together is that they made the move by choice, as a way to complement or enhance their solo work or, in the case of Manze, as an alternative to what they had done for much of their careers. But when Peter Oundjian made the switch in 1995, the violinist had no choice. He was diagnosed with focal dystonia, a neurological disorder that causes involuntary muscle contractions, in his case, in the all-important left hand. It ultimately made it impossible for him to play at the level necessary to continue serving as first violinist of the Tokyo String Quartet, one of the premier such ensembles in the world at the time.

Oundjian conducting the Orchestra of St. Luke’s and cellist Alisa Weilerstein at Caramoor in 2019 (photo: Gabe Palacio)

But he has gone on to have a second career as impressive as his first, including serving as music director of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra from 2004 through 2018 and heading the Royal Scottish National Orchestra for six years. In 2019, he took over as music director of the Colorado Music Festival and has quickly built its profile, adding a Music of Today mini-festival, which this summer features John Adams as composer-in-residence and co-curator. Indeed, Oundjian has enjoyed such success on the podium that many younger classical fans probably aren’t even aware of his earlier incarnation as a major chamber musician.

Ravinia Festival audiences will have a chance to see Oundjian the conductor in action when he joins violinist Itzhak Perlman, one of the most recognized classical musicians in the world, for an August 18 concert with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Perlman is among four star violinists and conductors who have intervened in Oundjian’s life at key moments and served as mentors to him. “What I’m impressed with is the way Peter was able to change careers, which for me is really an amazing feat,” Perlman said.

“I’m telling you now, you have the hands of a conductor.”

Born in Toronto to Armenian parents, Oundjian, 66, first became interested in the violin through Manoug Parikian, a former concertmaster of London’s Philharmonia Orchestra who was also of Armenian descent and a good friend of his father. When the violinist would visit, the boy would insist that Parikian play something before he went to bed. “So, I identified very much with the violin,” he said. But the youngster first started taking piano lessons when he was 6 and switched to the violin a year later, after his family moved to England. It turned out that there were too many pianists in the family—his father and his two sisters played the instrument. He also joined a boys’ chorus and appeared on a couple of Decca albums with Benjamin Britten as conductor, including a 1967 one featuring the composer’s opera A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream with the London Symphony. About 10 years ago, he discovered that he is shown in a photograph in materials accompanying the album playing what he called “Indian bells” in the fairy stage band when he was around 11.

After Oundjian graduated from high school and had been attending the Royal College of Music for one and a half years, his father pressured him to go to Salzburg to study, and that’s the point where the first of his famed mentors stepped in. Zukerman, then 26, was scheduled to give a master class at the Brighton Festival, and Oundjian got a call that one of the students scheduled to take part had fallen sick. Could he fill in? Of course, he said yes. At the end of the session, Zukerman said he should come to New York’s famed Juilliard School. But Oundjian explained that his father was insistent on Salzburg. So, Zukerman spoke to the parent, and after only a minute or so won him over to the idea of New York, insisting the he would look out for the young musician.

Itzhak Perlman and Pinchas Zukerman in 1978, when Oundjian was studying at The Juilliard School with their encouragement—a formidable duo of musical references (photo: Jack Mitchell)

Perlman entered his life around the same time. Oundjian reached out to philanthropist Ian Stoutzker, then-chairman of the Philharmonia Orchestra and an amateur violinist, asking to play for him before auditioning at Juilliard. Stoutzker told the young violinist he was going out of town on a business trip, but could he come over that night? Oundjian didn’t hesitate, traveling from one side of London to the other get there. When he was ushered in, he was amazed to see Perlman in the living room. “So, that’s how I met Itzhak and he was so delightful and so helpful,” Oundjian said. Perlman remembers the encounter and the “obviously very talented” young violinist. “What impressed me about him was, first of all, he is a very nice fellow,” Perlman said. “That always makes a difference to me.”

So, Oundjian came to New York with phone numbers of two of his musical heroes. “These, to me,” he said, “were the two most inspiring violinists alive, and I arrived in New York knowing them both somewhat, which was incredible.” Perlman told him to call if there were any problems, and there was a hitch right away. He had his heart set on studying with Ivan Galamian, who had been Perlman’s teacher and, who, not coincidentally, was Armenian American, but he was not at his Juilliard audition. In the end, things got sorted out, and Oundjian studied for three years with Galamian. Then after several months of study with Perlman at Brooklyn College, he returned to Juilliard with Perlman’s help to complete his training with Dorothy DeLay, another of the school’s revered teachers at the time. “The important thing is to support young people,” Perlman said, “and give them confidence that they can do things.”

Perlman and Oundjian rehearse Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins for a performance with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra in 2012. Then eight years into his tenure as the TSO’s music director, Oundjian remarked that it was his first public violin performance since his retirement from the Tokyo String Quartet. (photo: Dale Wilcox)

Although Oundjian had a trio at the Royal College of Music and regularly played chamber music with his family, he was intent to prove he could be a soloist. That everyone kept telling him how suited he was to the form only made him more determined. “You know,” he said, “the young ego says, ‘Thank you very much, but I can play the Sibelius Concerto just fine.’ ” He went on to win first prize at an international violin competition in Viña del Mar, Chile, and obtained representation by the once-prominent artist manager Harold Shaw. But, then, a week after selling out Carnegie Hall, the Tokyo String Quartet invited him to become its first violinist, an offer he couldn’t turn down. “I loved their playing,” he said. “It was unbelievable.” Oundjian joined the group during the same week he graduated from Juilliard in May 1981.

He enjoyed enormous success with the quartet, but its grueling schedule—140 concerts a year—began to take its toll on him physically. “The pressure started to build and my hand didn’t feel like it was moving normally,” he said. In October 1993, two of his fingers “collapsed” and he suspected what turned out to be the case: he was suffering from focal dystonia, the same condition that forced famed pianist Leon Fleisher to perform with just his left hand for many years. “I knew I had to get off the stage before I was booed off the stage,” Oundjian said. He managed to stay on with the quartet for another one and a half years, helping the group mark its 25th anniversary with performances of the complete set of Beethoven quartets all over the world, finally stepping down in 1995.

That same year, Oundjian, who has taught at Yale University since 1981, joined the faculty of the Steans Institute, Ravinia’s nationally known summer training program, where he returned each summer through 1999 and again in 2002, coaching both chamber groups and individual violinists. “I was always intent on teaching these people to play the violin in such a way that nothing would happen to them that happened to me,” he said. Too often, he said, musicians are told to practice intensely with little thought to the effects on the body. He exhorts his students to use their muscles in the right way and not use more strength than is necessary to accomplish each movement. “Most musicians who want to do this are not as patient as they might need to be when they are practicing. They try to force themselves to get to a certain level a little more quickly than they should.”

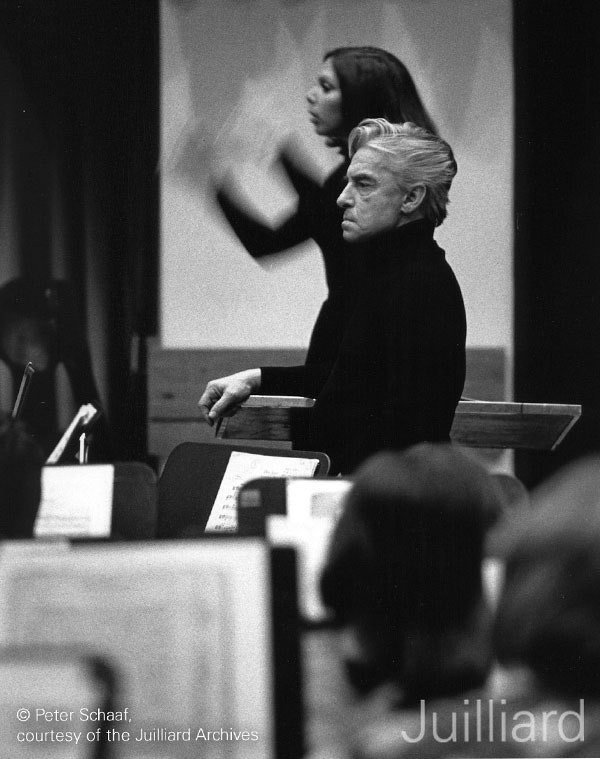

In 1976, Herbert von Karajan, then 20 years into his lifetime appointment as principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, led three days of master classes for the conducting program at The Juilliard School with the student orchestra. Perhaps frustrated by the young conductors’ over-preparation, during the second session he put the orchestra’s concertmaster—one Peter Oundjian—on the podium to lead purely from his experience of playing the music. (photo: Peter Schaff)

After leaving the Tokyo String Quartet, the big question was what to do next. He had a family to support and a mortgage to pay. To find an answer, he looked back at a significant experience at Juilliard, when he crossed paths with another mentor. Celebrated conductor Herbert von Karajan came to give master classes, and Oundjian served as the concertmaster of the participating orchestra. Karajan asked him if he conducted, and, in fact, Oundjian was a conducting minor. The conductor left 20 minutes at the end of the second session for Oundjian to lead Brahms’s First Symphony, and his fellow players worked hard to make the stand-in conductor look good. “I’m telling you now, you have the hands of a conductor,” Karajan told the young violinist.

Those words came echoing back in 1995, and Oundjian decided to give conducting a try. The first person he told about his idea was another noted conductor and friend, André Previn. The maestro had Oundjian over to his house and shared some of the things he would need to know, including some of the tricks that musicians would play on unsuspecting conductors. “It was incredible,” Oundjian said. Previn allowed the former violinist to share the podium during a concert as part of the 50th anniversary season of the Caramoor Center for Music and the Arts near Katonah, NY. That outing went so well that the aspiring conductor went on to serve as the organization’s artistic director from 1997 through 2003 and artistic adviser and principal conductor from 2004 through 2007.

Jeffrey Haydon, who took over as president and chief executive officer of Ravinia in 2020, had held a similar position at Caramoor, where he quickly became aware of Oundjian’s prior impact there. “He did an amazing job of raising the profile of Caramoor,” Haydon said. When Haydon arrived there in September 2012, little was on the books for 2013, so he decided the summer season needed a big orchestral concert featuring someone with special meaning to the festival. “Very quickly, all eyes went to Peter Oundjian,” Haydon said. He called up the conductor, who maintains a residence about 35 minutes from the grounds, and Oundjian quickly agreed.

Jeffrey Haydon (right), while CEO of Caramoor, regularly welcomed Oundjian as a guest conductor at the festival, including at its 2019 gala concert with Weilerstein—what would be his last before taking the similar position at Ravinia and again calling upon the conductor. (photo: Gabe Palacio)

When Haydon and Marin Alsop, Ravinia’s chief conductor, were planning the 2022 Chicago Symphony season, they shared lists of conductors they wanted to see at the festival. One name on both lists was Oundjian’s. Alsop and he were classmates at Juilliard and both played together in the same student orchestra. “I’ve known her for ages and I’ve always liked her and always admired her,” he said. When Alsop served as music director of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra from 2007 through 2021, Oundjian was a guest conductor 10 or so times, and he now serves as principal conductor of the Colorado Symphony, which Alsop led early in her career.

Perlman is not often able to perform at Ravinia with the CSO, because the summer institute of the Perlman Music Program, which the violinist founded with his wife, Toby, usually conflicts. But this year the timing worked out that Perlman could come, and he will perform Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto. “This is a rare moment to see him perform live,” Haydon said. The Ravinia leader asked Oundjian if he would be willing to lead the concert, not knowing the history between the two performers, and, the conductor jumped at the chance, having shared the stage with his old friend many times before, including at his last Ravinia appearance in 2004. “He is an extraordinary person on many, many levels,” Oundjian said of Perlman. “I can’t believe what he gives to all of us. To be on the stage with him is just a thrill.” ●

Kyle MacMillan served as classical music critic for the Denver Post from 2000 through 2011. He currently freelances in Chicago, writing for such publications and websites as the Chicago Sun-Times, Early Music America, Opera News, and Classical Voice of North America.