By Laura Emerick

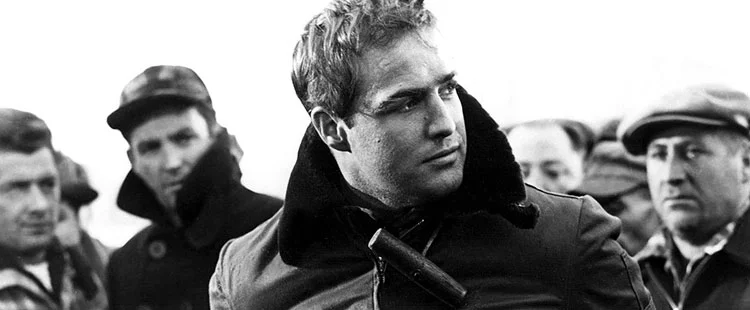

In his autobiography A Life (1988), director Elia Kazan outlined the reasons “On the Waterfront” (1954), universally regarded as his greatest film, was a success. Singling out his lead actor, Marlon Brando (as conflicted longshoreman Terry Malloy), screenwriter Budd Schulberg and producer Sam Spiegel, Kazan was effusive in his praise: “If there is a better performance [than Brando’s] by a man in the history of films in America, I don’t know what it is. Then there was Budd’s devotion and tenacity and his talent. He never backed off. I was tough and good on the streets and persisted through all difficulties. But finally there was Sam. After the casting of the main part had been settled, the rewriting process began, and it was here, above all, that Sam showed his worth.”

Curiously, Kazan failed to mention Leonard Bernstein’s music, the only score that the American composer-conductor ever wrote specifically for a film. “On the Waterfront” received 12 Academy Award nominations, including one for its score; it won eight Oscars, including best picture, director, screenplay, cinematography, and of course, actor. Bernstein lost to Hollywood veteran Dimitri Tiomkin for “The High and the Mighty” — a plane-in-peril drama with a popular soundtrack (John Wayne, as the movie’s hero, whistles the title theme throughout the film). With its tortured history, however, “On the Waterfront” was a surprising Oscar winner, and remains a polarizing film in some quarters to this day.

Many viewed the film’s subject — corruption on the East Coast docks — as Kazan’s allegorical response to his naming names during the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings in 1952. Because of Kazan’s pariah status, Brando and Bernstein initially refused to work with him on “Waterfront.” As newcomers, Eva Marie Saint (as Edie Doyle, Terry’s love interest) and Rod Steiger (as Charley, Terry’s brother, and underling of corrupt union boss Johnny Friendly, played by Lee J. Cobb) presumably were in no position to object to Kazan’s politics. (During a session at the 2013 TCM Classic Film Festival, Saint recalled that “at the time there wasn’t discussion about it.”) Karl Malden, as the crusading priest Father Barry, regarded Kazan as a mentor after their days together at the Group Theatre in the late ’30s and refused to denounce a man he considered “a dear friend.”

Despite the motivations of Kazan and Schulberg (another HUAC friendly witness), the film’s artistry rises above any personal agenda. Chief among the movie’s artistic achievements is Bernstein’s score, which many consider among the most distinctive in Hollywood history. Jon Burlingame, a leading writer on the subject of film and television music and an instructor in film-music history at the University of Southern California, is one of the score’s avid champions. He discusses Bernstein’s work in a visual essay featured on the 2013 Criterion Collection edition of “On the Waterfront”; he also authored the chapter about the film’s score in Cambridge University Press’ 2003 book devoted to the film. Ahead of the CSO at the Movies screening Oct. 23 of “On the Waterfront,”Burlingame explains what makes Bernstein’s score so extraordinary.

The soundtrack elevates the film and becomes virtually another character in the drama. As with, say, Bernard Herrmann’s score for “Vertigo,” the music is integral to the film’s impact. Why is this so?

JB: Unlike most film scores of the 1950s, the music of “On the Waterfront” is really a full partner in the filmmaking process, matching the script, direction and acting in conveying the essence of the drama. Bernstein’s score is brilliantly designed, offering a quietly noble theme for Terry (Marlon Brando), a touching love theme for Terry and Edie (Eva Marie Saint), and an angry, visceral theme for the violence in and around the waterfront, usually the work of the corrupt union bosses. Bernstein’s music helps us — sometimes in an unconscious way — understand the relationship between all these elements.

How was Bernstein’s music such a departure from the typical Hollywood score of its era?

JB: First, producer Sam Spiegel really wasn’t interested in what music could do for the film; he wanted a “big name” on the poster to help sell the picture and bring added promotional value to the project. Leonard Bernstein was the biggest name in American classical music at the time. Second, he’d never done a film before, so he didn’t give a second thought to opening the film with a single instrument (a lonely French horn), practically unheard-of in an era when movies generally started with the whole orchestra blaring away. The surprising casting of this musically brash New Yorker, and the undeniably fresh approach he brought to the movie, shook up the status quo.

In your writings about this film, you identify three major themes; what other important music moments should audience members listen for?

JB: There are several: the initial appearance of the violence theme, right after the opening titles, as Joey (Edie’s brother) is murdered; the love theme (as Terry walks Edie home from the park, then again when Terry and Edie are on the roof with his pigeons); the end of Father Barry’s sermon, as he’s lifted out of the cargo hold, where Bernstein plays a funereal adaptation of the violence theme; the sorrowful music heard as Terry discovers all his pigeons have been killed, which leads directly to his decision to return to the waterfront, accompanied (for the first time since the opening of the film) by his theme, and the final four minutes of the film, as Terry leads the longshoremen into a new day’s work while Bernstein intertwines his theme and the love theme, concluding with a powerful statement for orchestra.

“On the Waterfront” is dialogue-heavy, which at some points, impeded the inclusion of music; how did Bernstein work around that aspect?

JB: Every film composer must negotiate the tricky balance among sound elements (dialogue, natural sound, music), but Bernstein “pushed the envelope” more than most. When he felt that music needed to come to the fore, he didn’t shy away from the challenge, and very often he found a way for the dialogue and music to share the aural space on the soundtrack.

The film’s most famous scene is Terry Malloy’s “I coulda been a contender” soliloquy; how does Bernstein’s music contribute to the scene’s pathos — and sincerity?

JB: It’s also one of the most famous scenes in all of movie history, and Bernstein both supports and bolsters its emotional impact with his music. As Terry and Charley debate the sad details of Terry’s failed boxing career, the composer reprises the dirge-like music from that earlier scene of Father Barry in the cargo hold, and when the cab races off, those swirling strings and sharp brass of the violence theme return and Charley’s doom is sealed.

Sixty years after its release, the film’s most enduring achievements remain Brando’s performance and Bernstein’s score, and yet when the film is discussed nowadays, it’s usually in the context of being Kazan’s apologia for naming names or for Brando’s Oscar-winning portrayal. Why has Bernstein’s triumph been somewhat forgotten over time?

JB: It’s a shame that the brilliance of “On the Waterfront” has been overshadowed by the persistent Kazan controversy. But I certainly understand people remembering Brando’s towering performance (along with those of Eva Marie Saint, Karl Malden and Rod Steiger). Anyone who knows the film appreciates Bernstein’s contribution, and live-to-picture events like this one will help to remind people just how thrilling and significant it is.

Kazan and Schulberg even criticized or downplayed Bernstein’s work. Kazan complained that the score “put the picture on the level of almost operatic melodrama here and there”; Schulberg, while acknowledging “it was a marvelous score,” thought the music at times “was too loud, it was sometimes outdoing the dialogue or telling too much.” Do these criticisms have any merit?

JB: In a word, no. Filmmakers often fear the addition of music, thinking it will distract or be otherwise intrusive. In fact, the best scores elevate a film — deepening the psychology of the characters, helping us to feel the appropriate emotions, dramatically underlining the narrative at the appropriate moments. Once in a great while a movie becomes an artistic triumph, and Bernstein’s music definitely lifts “On the Waterfront” into that realm.

After “Waterfront,” Bernstein never scored another film because he had no interest in writing “background” music, as he put it. If he had won the Oscar, would he have changed his mind?

JB: That’s hard to say. He should have won the Oscar, in my view, and its brilliance is such that nearly all of the other nominees that year are forgotten today. “On the Waterfront” lives on not only within the film but as a frequently performed symphonic suite for the concert hall. In fact, Bernstein was irritated that two of his cues were dropped from the final version, and in one or two cases the music was dialed down in volume more than he liked. Bernstein was an artist, and his assistant told me many years later that this lack of control over the final product was more than he could stand. That was unlikely to change in the movie world, so he never tackled another one.

Where does “On the Waterfront” rank in the pantheon of all-time great film scores? If Bernstein had somehow been persuaded to take on another film project, which film would you have chosen for him and why?

JB: Of course, there are many great film scores throughout Hollywood history. I’m not a big believer in lists or rankings, but the American Film Institute places it among the top 25 greatest scores of all time. I won’t argue with that. As to the second question: Director Franco Zeffirelli wanted Bernstein to score his six-and-a-half-hour miniseries “Jesus of Nazareth” (1977), and it’s an intriguing proposition. French composer Maurice Jarre (“Lawrence of Arabia”) ultimately scored it, but I can’t help wondering what Bernstein might have written for the greatest life of Christ ever put on film.

This story is a repost courtesy of CSO Sound & Stories.