A fractured history belies Alma Mahler’s devotion to her own creation

By John Schauer

Less than six months after the death of Alma Schindler on December 11, 1964, the satirical songwriter Tom Lehrer wrote a song that he said was inspired by “the juiciest, spiciest, raciest obituary it has ever been my pleasure to read.” Worth checking out on YouTube, his ballad “Alma” is highly entertaining but does little justice to a figure who has frustrated historians attempting an accurate portrait.

Alma Schindler, born August 31, 1879, in Vienna, has come to be seen in two different guises. Long famous primarily for her marriages to and affairs with celebrated and creative men, she has, on the one hand, been lionized as a female incarnation of inspiration, and on the other derided as a promiscuous fin-de-siecle groupie. As one of her biographers, Oliver Hilmes, summarized, “For one camp, she is the muse of the four arts; for the other an utterly domineering and sex-crazed Circe, who exploited her prominent husbands exclusively for her own purposes.” (Hilmes went so far as to title his biography Malevolent Muse.) Viennese journalist Marietta Torberg (1920–2000) declared, “She was a grande dame and at the same time a cesspool.” Even her own daughter Anna (1904–1988) recognized the dichotomy: “I used to call her Tiger-Mommy. And now and then she was magnificent. And now and then she was absolutely abominable.”

To understand the contradictory nature of this remarkable woman, we need to take into account the remarkable society that shaped her and was, in turn, shaped by her. Like Alma, Vienna had two distinct natures in the decades preceding the First World War. One was the whipped-cream-and-operetta Vienna of popular imagination—prancing Lipizzan stallions, Strauss waltzes, fairy-tale rococo palaces, and a flair for pastry unsurpassed anywhere in the world.

But Vienna also had a darker aspect during the years that Alma lived there. The Imperial City was the capital of an empire that existed more in theory than practice, and the growing nationalism of its constituent countries would ultimately lead to the collapse of the empire shortly after the start of the war. The denizens of Vienna, it used to be said, were “dancing on the rim of the volcano.” As one observer put it, the situation in most European capitals at that time was serious, but not hopeless; in Vienna, it was hopeless, but not serious.

“I have been firmly taken by the arm and led away from myself.”

The chasm that separated the lower class from the upper class was enormous, and vast portions of the Viennese population lived in appalling squalor even as the emerging merchant middle class was settling into its impressive apartments along the newly constructed Ringstrasse that replaced the city’s old medieval walls. These recently prosperous citizens increasingly turned their attention to artistic and intellectual pursuits, with the result that Vienna was unmatched as an incubator of exciting new developments in the realms of design, graphic arts, architecture, literature, theater, and music. The plethora of creativity in Vienna at that time can perhaps diminish somewhat the pejorative notion of Alma as a predatory seductress on the prowl for famous men. In the social circles she moved through, it would have been difficult for Alma not to encounter creative geniuses; and as she was known for her wit, intellect, and musical talent, in addition to being regarded as the most beautiful woman in Vienna, it was inevitable that many of them would become attracted to her on their own.

One of the first was artist Gustav Klimt. In her diary entry for February 9, 1898, Alma wrote, “If only I were a somebody—a real person, noted for and capable of great things. But I’m a nobody, an indifferent young lady who, on demand, runs her fingers prettily up and down the piano keys and, on demand, gives arrogant replies to arrogant questions … just like millions of others. Nothing pleases me more than to be told that I’m exceptional. Klimt, for instance, said: ‘You’re a rare, unusual kind of girl, but why do you do this, that, and the other just like everyone else?’ … I want to do something really remarkable. Would like to compose a really good opera—something no woman has ever achieved. In a word, I want to be a somebody. But it’s impossible—and why? I don’t lack talent, but my attitude is too frivolous for my objectives, for artistic achievement. Please God, give me some great mission, give me something great to do! Make me happy!”

Alma and Gustav Mahler visited Basel, Switzerland, in 1903 for Gustav to conduct his Second Symphony on June 15 at the 39th Music Festival of the General German Music Society. Taken on the Rheinsprung overlooking the river Rhine, this is one of the first known photos of the Mahlers together, just over a year after they were married.

Although she and Klimt did become infatuated with each other—she is said to have been the inspiration for his paintings of Pallas Athena and Judith (also known as Salome)—their affair apparently never progressed beyond passionate kisses on two occasions. But her relationship with her composition teacher Alexander von Zemlinsky would be much more physical, despite his own unfortunate appearance. On February 26, 1900, she recorded, “This evening at Spitzer’s. I went with the greatest disinclination—and had a wonderful time. Spoke almost all evening with Alexander von Zemlinsky, the 28-year-old composer of ‘Es war einmal.’ He is dreadfully ugly, almost chinless—yet I found him quite enthralling.” After the two of them engaged in viciously dishing about some singer, Zemlinsky said to her, “If we can think of someone with whom neither of us has a bone to pick, we’ll down a glass of punch in their honor.” As Alma records, “After a while we did indeed think of somebody: Gustav Mahler. We drained our glasses. I told him how greatly I venerated [Mahler] and how I longed to meet him.”

Alma seems to have vacillated between physical passion and revulsion for Zemlinsky but ultimately dumped him in November 1901 after she made the acquaintance of Mahler, who, at least in Alma’s account, told a friend, “I didn’t care for her at first. I thought she was just a doll. But then I realized that she’s also very perceptive. Maybe my first impression was because one doesn’t normally expect such a good-looking girl to take anything seriously.”

She certainly took Mahler seriously, and barely three months later they were married, by which time she was already pregnant. They had musical commonalities; both worshipped the music of Richard Wagner, whose operas had been the vehicles of some of Mahler’s greatest conducting triumphs, and Alma reportedly was able to play a piano reduction of the complete Tristan und Isolde from memory. Unfortunately, Alma also emulated Wagner’s infamous anti-Semitism, which is particularly ironic considering that two of her three husbands—Mahler and later Franz Werfel—were Jews.

Prior to their marriage, Mahler famously sent Alma a 22-page letter in which he made it clear that she would have to abandon her own composition activities: “The role of composer, the worker’s role, falls to me; yours is that of a loving companion and understanding partner.” Alma’s acquiescence set the stage for the dynamics that would strain their marriage nearly to the breaking point, and she sadly wrote, “I have been firmly taken by the arm and led away from myself.”

Alma had two children with Gustav, Maria Anna (“Putzi,” on the left, born 1902) and Anna Justine (“Gucki,” on the right, born 1904). Maria, sadly, died of either scarlet fever or diphtheria in 1907, about a year after this photo was taken.

It was during the time of their whirlwind courtship and first year of marriage that Gustav composed his Fifth Symphony, and the famous Adagietto has been said to be a love-letter to his bride. Perhaps it was frustration of her creative instincts that eventually led Alma into an affair with the founder of the legendary Bauhaus school of design, Walter Gropius. In 1910, having learned of Alma’s affair, Gustav became consumed by anxiety that she was about to leave him and reluctantly sought counseling from none other than Sigmund Freud. The two living legends met at a spa in Leyden and are reported to have walked and talked for four hours. In a 1934 letter to Theodor Reik, Freud wrote, “The visit appeared necessary for him, because his wife at that time rebelled against the fact that he withdrew his libido from her. In highly interesting expeditions with him through his life history, we discovered his personal conditions for love, especially in his Holy Mary complex …” Freud’s mention of the “Holy Mary complex” is particularly insightful considering that only three weeks after their meeting, Gustav would conduct the premiere of his Eighth Symphony, the second half of which is a celebration of the Mater Glorioso, or Virgin Mary, and the “eternal feminine.” Gustav wrote to Alma afterwards that the session left him “filled with joy.”

“I want to do something really remarkable. Would like to compose a really good opera—something no woman has ever achieved. … Please God, give me some great mission, give me something great to do! Make me happy!”

To win back his wife’s affection, he now encouraged her to compose, and even edited and arranged for the 1910 publication of her Five Songs (four of which will be performed on July 19 along with Mahler’s Fifth Symphony). But it may have been too little, too late, and even as he rehearsed for the premiere of his Eighth Symphony, her assignations with Gropius continued. Gustav, who had been diagnosed with a serious heart ailment, died in May of the following year.

Oskar Kokoschka’s best-known work, Die Windsbraut (1914; The Bride of the Wind or The Tempest), is a self-portrait of the painter lying alongside the recently widowed Alma, created shortly after their meeting in 1912.

Alma would marry Gropius on August 18, 1915, but not before engaging in a tempestuous affair with the artist Oskar Kokoschka, who immortalized her in his painting The Bride of the Wind (also the title of a dreadful 2001 film biography of Alma). But while he was serving in the Austrian army during the First World War, she abandoned him to return to Gropius. Kokoschka, who would later claim that Alma had aborted his child, subsequently had a life-size, anatomically correct doll constructed to look like Alma, and he actually would appear in public with it at cafés or the theater.

After she married Gropius, Alma gave birth to a baby boy in 1918, but the story told in gossip-loving Vienna was that it was actually the love-child of writer Franz Werfel, with whom she had begun an affair in the fall of 1917; she and Gropius divorced in October 1920. She lived openly with Werfel for years, finally marrying him in 1929, but the onset of the Second World War forced them to flee ultimately to California, where a couple of Werfel’s works were converted to Hollywood films and where she presided over stellar gatherings that included the likes of Max Reinhardt, Igor Stravinsky, Benjamin Britten, Bruno Walter, and Thomas Mann. Following Werfel’s death in 1951, Alma moved to New York, where she lived the rest of her life in a two-room apartment.

The headline of her obituary in the New York Times listed her as “Alma M. Werfel, Widow of Writer,” but today she is most frequently referred to as Alma Mahler, despite her two subsequent husbands and that, during the 50 years that she outlived the composer, she worked assiduously to manipulate the historical record of their relationship, fabricating records, forging portions of his letters to her, destroying all but one of her letters to him, and writing a rather fanciful volume of memoirs. Her PR campaign was so thorough and difficult to discern that historians have actually coined the term “The Alma Problem” to describe their predicament. As her own daughter exclaimed to a biographer of Franz Werfel, “If you were planning on using my mother’s memoirs as a basis for your research, then you should forget the whole project right here and now.”

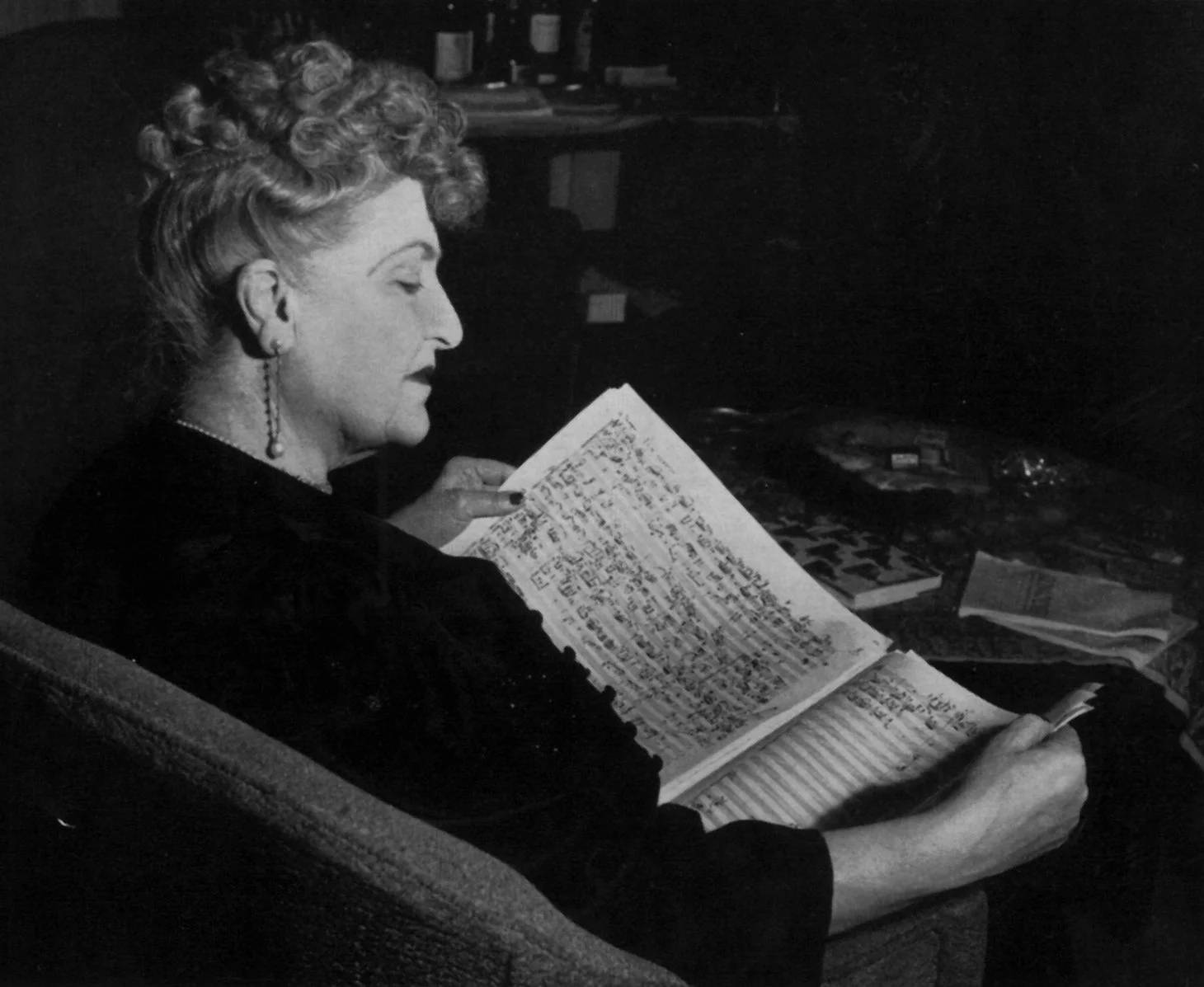

Today musicologists are beginning to focus less on the verbal record and more on the musical one. Alma wrote some 50 songs—or even twice that, by some accounts—but only 14 are still extant. Dianne Follet, who has taught women’s music history at Muhlenberg College, wrote, “Her songs, perhaps even more than her writings … reveal Alma’s true nature. They verge on the melodramatic, as did Alma; they are complex, as was Alma; they are contradictory, as was Alma. It is in her songs that we meet her, and it is through her songs that she assumes her rightful place.”

Perhaps we should give Alma the final word. In November 1901, she wrote, “A new idea occurred to me: art is the outcome of love. While love, for a man, is a tool for creativity, for a woman it’s the principal motive.” ■

Currently a freelance writer, John Schauer was formerly the editor of Ravinia magazine for 22 years. Alma diary quotes are from the translation by Antony Beaumont.