By John Schauer

As a Baby Boomer, I grew up in Milwaukee, WI, at a time when the city didn’t yet have a symphony orchestra. The Three Bs in Milwaukee at that time weren’t Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms; they were beer, bratwurst, and bowling. Despite its many inaccuracies, the sitcom Laverne and Shirley got a surprising amount right in its depiction of middle-class Milwaukee.

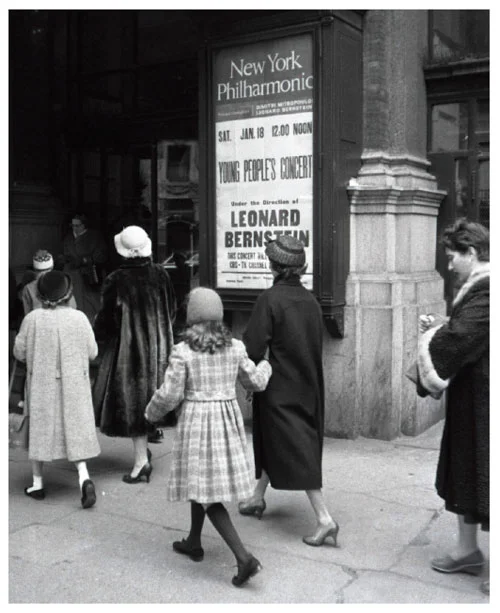

At a very young age, I had already become a classical music snob, thanks to piano lessons and a (pathetically) small collection of LPs. So it was a memorable afternoon when my mother summoned me and my sister into the living room to watch the first of Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts. There, in Carnegie Hall, what must have been the world’s most blessed children were being initiated into the universe of classical music by the world’s most celebrated conductor. You can barely imagine my ire when the camera would zoom in on some kid who had fallen asleep in his seat—what an affront, what an arrogant display of privilege, to be able to sleep in the most iconic concert hall in the US, in the presence of the New York Philharmonic!

I must confess that today, when I review Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts on DVD, I realize how much of those talks may have gone over my head when I was still in grade school, with the sobering realization that had I actually been seated in Carnegie Hall, I might have fallen asleep myself. But back then I was driven by a Laverne DeFazio determination to prove that Milwaukee youngsters could appreciate classical music as much as, if not more than, those highfalutin New Yorkers.

It would be difficult to describe my wild excitement when I learned years later that Bernstein was going to conduct the New York Philharmonic in Milwaukee—and that most of the tickets were being given away! I of course instantly sent in my self-addressed, stamped envelope, and in due time I did receive a pair of tickets. To illustrate the Laverne-and-Shirley flavor of the event, it was to be given in the Blatz “Temple of Music” bandshell in Washington Park, and the whole shebang was being sponsored by the Uihlein family, which owned and ran the Schlitz Brewing Company. Even my first encounter with Leonard Bernstein would be tinged with beer.

The best seats up front were sold at high prices, of course, and the free bench seats at the back of the park were so far away you could only hear the orchestra over loudspeakers. Unfortunately, the art of outdoor amplification was nowhere near what it is today, and the sonics were comparable to a cheap, monaural phonograph, but that didn’t dampen my enthusiasm, which was thrown into overdrive when I saw that the program included Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. This was a work I had come to know from the legendary Bernstein recording I had played incessantly—on a cheap, monaural phonograph—until I knew every note.

At the end of the concert, I raced up the aisle to get a better look at the maestro, but as I got near the stage, Bernstein came back out to lead an encore, so I sat down on the ground and had my first up-close experience of an orchestra as Bernstein pulled out all the stops for a heart-pumping rendition of “The Stars and Stripes Forever.” Sousa, not Stravinsky, would be my true baptism by live symphonic music.

After Bernstein walked offstage, I could see him in the wings, wrapped in a cape and holding a cigarette. In a manner uncharacteristic of me, I impulsively rushed past the stage guard and thrust my program at Bernstein for an autograph. Without a word he promptly pulled out a pen and signed the program that hangs in my living room today.

That concert’s legacy is more than a framed artifact on my wall; the overwhelming response of Milwaukee’s denizens inspired the Philharmonic’s management to establish their annual series of free concerts in New York’s Central Park. So smug New Yorkers should be humbled to know that before he was conducting in Central Park, Lenny was bangin’ it in Beertown.

Laverne and Shirley would be proud. ▪

John Schauer is a freelance writer and dedicated dog-owner who surprisingly has never been all that fond of beer.