One Big Beautiful Sound

By Web Behrens

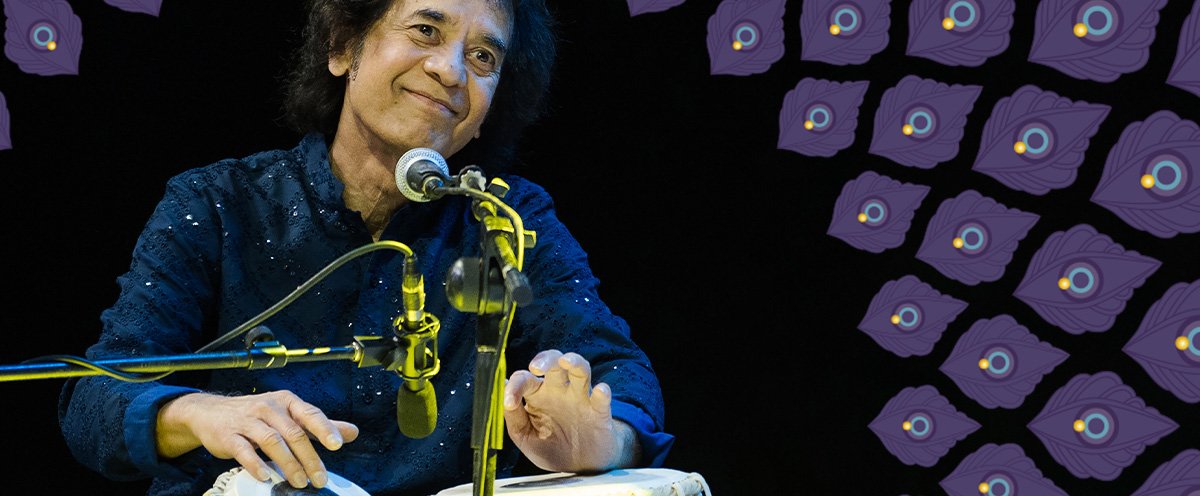

World-renowned tabla virtuoso Zakir Hussain remembers exactly when he first made music with guitar legend John McLaughlin. It was September 1972 in the Bay Area, and Hussain had been jaw-droppingly gobsmacked the night prior by McLaughlin, shredding up a storm in concert with his jazz-fusion band. The following day, they were hanging out at the home of maestro Ali Akbar Khan when McLaughlin asked Hussain, “Would you play with me?”

The 30-year-old Englishman picked up his acoustic guitar; the 21-year-old Indian prodigy availed himself of Khan’s tabla (a pair of hand drums used for centuries in North Indian classical music). “It was like we’d been doing this for the past 50 years,” Hussain recalls during a lengthy but utterly engaging interview with Ravinia.

The original quartet of Shakti (right to left): Zakir Hussain, John McLaughlin, L. Shankar, and Vikku Vinayakram

“It was right,” he continues. “Our minds as one; our path, rhythmically, as one, starting and stopping together, knowing instinctively what the other person was about to do. It was about as close to perfect as one could imagine. John and I both knew we had to make music together.”

Thus was a legend born: Shakti, the trailblazing improvisational band that to this day remains one of the greatest musical unions of East and West. The initial lineup comprised four musicians: McLaughlin, Hussain, violinist L. Shankar, and another percussionist, Vikku Vinayakram. “We got together in New York and, after a one-hour rehearsal, we did our first concert,” Hussain says. The initial output was instrumental, but this long-lasting ensemble expanded and contracted over the decades, sometimes adding vocals, mandolin, flute, or other sounds.

This flexibility means that the group never truly disbands. Shakti simply goes fallow, then reforms and rises anew. “We never felt that what we’re doing has an ending,” Hussain observes. “It keeps moving. It doesn’t matter if we don’t get together for three or four years. When we come together to play, we take up from where we left off, no hurdles, no hiccups. Over the years, we’ve done different projects away from each other, but we always gravitate back together, that much more enriched from our various relationships with other musicians.”

The present Shakti quintet (clockwise from left): Hussain, violinist Ganesh Rajagopalan, McLaughlin, Bollywood singer-composer Shankar Mahadevan, and virtuoso Carnatic percussionist Selvaganesh Vinayakram

Half a century after that first jam session, McLaughlin and Hussain have launched a golden-anniversary world tour. It kicked off in India in January before heading to Europe, and now winds through the United States. In a big surprise for their fans, Shakti—a band mostly known for its concerts and live recordings—also recently released This Moment, the first new studio album in 45 years. Another fun surprise: their September 3 concert at Ravinia includes an appearance by banjo sorcerer Béla Fleck, with whom Hussain recently renewed a trio collaboration including bassist Edgar Meyer for the album and upcoming tour As We Speak.

This latest Shakti incarnation, now a quintet, retains one-half of its original lineup, Hussain and McLaughlin. But there’s another special connection brought by the presence of a second percussionist, Selvaganesh Vinayakram. He’s the son of original Shakti member Vikku, which further weaves together the varied strands from the band’s long history.

“When Selvaganesh joined Shakti, from the very first point on, it was like I was playing with his father,” Hussain says. “He knew the patterns; he knew the looks. Vikku Vinayakram and I had a kind of chemistry. Selvaganesh grew up watching that. He can read my eyes exactly like Vikku did.”

Not only a percussionist, Selvaganesh is also a composer and sound engineer in his own right. “He has his fingers in technology to enhance the sonic experience,” Hussain adds. “He will ask me, ‘Zakir, why don’t we try this? If we use this microphone and this reverb, your tabla is going to sound like so-and-so.’ Lo and behold, it’s a new experience playing with him—not only rhythmically and compositionally, but also sonically. That adds a different layer to the present Shakti.”

“Clive Davis persisted: ‘We have to tell the record store which bin to put the record in.’ John and I looked at each other and said, ‘We don’t know; it’s just music.’”

It’s natural that the group still finds ways to innovate, because that’s been their raison d’être since the beginning. Now considered a cornerstone of the amorphous “global music” genre, Shakti began producing its signature blend of East and West before there was even a name for their sound. “At that time, there was no fusion music, no New Age, no World Music, no nothing,” Hussain recalls. “I guess Shakti was at the forefront of getting that process started.”

He remembers first confronting the question of how to categorize their music in their early days, when they played their first recording for Clive Davis, the famous producer at Columbia/CBS Records. “He said, ‘Okay, what is this music?’ John and I looked at each other and said, ‘We don’t know; it’s just music.’

“Clive Davis persisted: ‘But John, I have to tell my PR team how to sell it. We have to tell the record store which bin to put the record in. You’ve got to give me an idea of what to call it.’ John said, ‘We don’t know. Call it whatever you want to call it.’ So we released the first Shakti album with no label on it regarding style of music.”

Listening to Hussain share vivid anecdotes from his 72 years, it becomes easy to understand how he became a world-class artist and syncretic musician. He’s the eldest son of legendary tabla player Alla Rakha, so his exposure to traditional Indian music began from birth. Furthermore, he was educated with an impressive (even stunning) commitment to understanding diverse perspectives and respecting Hindu, Muslim, and Christian theologies.

He also developed a deliciously dry sense of humor. “I was born in a small little sleepy town called Bombay,” says Hussain, who now lives with his wife in Marin County, just north of San Francisco. The city of his childhood, with about 3 million residents, is very different from today’s Mumbai, whose estimated population exploded by a factor of seven or eight since the mid-20th century, making it one of the most densely populated cities on earth. After we share a chuckle over his joke, Hussain clarifies, “Seriously, in 1951, it was a coastal town with nice beaches and a clean ocean, and hardly any cars on the road. But that’s all changed.”

As the son of an accomplished Indian musician, Hussain says his career path was predestined. He then shares a story about arriving home when he was two days old: “My mother presented me to my dad. The tradition is for the father to recite a prayer in the ear of the child, so my father took me in his arms—but instead of reciting a prayer, he recited rhythmic syllables. My mother was livid. She said, ‘Why are you doing this? You’re supposed to say a prayer to bless him!’

“My father said, ‘This is my prayer. This is how I pray; this is how he will pray.’ From there on, he would hold me in his arms for an hour or whatever, and just sing rhythms in my ear.”

Flash forward some years, when young Zakir played tabla for 10 minutes at a school concert. Impressed, his father asked him if he wanted to study the instrument seriously, and of course he said yes. “So my father said, ‘Tomorrow we will begin.’ And tomorrow was 3 o’clock in the morning. He woke me up, and we walked to the shrine of a Sufi saint while the world slept.”

Thus began a new phase of education. For a year or so, father and son would sit at the nearby shrine—not to play music, but to talk about it. “He was teaching me the reverence that goes with it, the whole history. I would spend a few hours with him, then my mother would come looking for us, bring me back, and shove some breakfast into me.”

Once his belly was full, the boy studied the Koran for an hour before heading to a Catholic high school. “So in the space of a few hours every morning,” he explains, “I would go through so many different ways of life. I’d be studying Hindu mythology, then to the Islamic system, then to holding a Bible in my hand. But in none of those moments was I ever made to feel by the masters involved that their way was the right way. I grew up learning that all of this was really just one thing, just different shades of thinking. That, I think, was a really fortunate way to grow up. It’s helped me tremendously to find my way in this world.”

Through a singular mix of natural talent and incredible dedication, Hussain began notching incredible achievements very early in life. His father had a long collaboration with Ravi Shankar, the legendary composer and sitar player, which became the genesis of Hussain’s first trip to the States. Shankar and Alla Rakha had achieved an amazing level of success in the Western Hemisphere, riveting audiences at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 and Woodstock in ’69. But in early 1970, before a concert at Fillmore East, the elder tabla player fell ill—so Shankar summoned the junior Hussain to New York to fill in. With his 19th birthday still two weeks away, Hussain made his US professional debut.

Another life-changing encounter happened in early 1973, just a few months after Hussain and McLaughlin discovered their musical chemistry. George Harrison was recording Living in the Material World, his third album in his artistically fecund post-Beatles era, and he recruited Hussain to perform on the title track. At some point during the recording, Harrison led him to an epiphany.

“I wanted to be a rock and roll drummer. I wanted to wear those jackets and have that hair, you know, to play in a band and be a star,” Hussain reminisces. “We were in Trident Studios in London, and I told George Harrison that. George said to me, ‘Zakir, you’re sitting next to me because you have something unique to offer. You’re a tabla player who represents an ancient tradition, who also validates it in the modern world. If you want to be a drummer, I have 500 drummers waiting outside this studio. Why do you want to be number 501?’ ”

Then Harrison made a suggestion: “Why don’t you transpose all these incredible rhythmic ideas onto your tabla? Turn your tabla into a rock drum, into a jazz drum, into a Latin drum, into an African drum. Become so unique, so special, that everybody wants to work with you.”

“That one talk with him, it was like a bulb turned on in my head,” he continues. “He really turned me around, and pushed me back to my roots. I realized for the first time how important Indian classical music was to me, and how I could take that and reinvent myself to wear all these different hats. That one lesson from George got me to a place where I could work with all these other musicians—Shakti, Van Morrison, Mickey Hart, Charles Lloyd, Béla Fleck, Edgar Meyer—and offer them what they wanted.”

“Selvaganesh has his fingers in technology … it’s a new layer to the present Shakti, playing with him—not only rhythmically and compositionally, but also sonically.”

And what a path he’s forged since then. Hussain’s many honors include titles from the governments of India, the United States, and France; honorary degrees from universities from Mumbai to Princeton; accolades from private institutions from Kyoto to San Francisco; and, yes, a Grammy Award for Best Contemporary World Music Album.

“When you talk about music fraternity, it doesn’t matter where in the world you are. There are no boundaries or fences in that way,” he says. “Edgar Meyer or Mickey Hart, they are of Jewish background, but they’re dear friends and we play music together. Ravi Shankar was a Hindu and my father was a Muslim, and it didn’t matter. They were a team together for so many years, like brothers. I can go to Japan, to Sado Island, and work with taiko drummers, and their zen system will allow me to be a part of it. Religion doesn’t come into place.

“It’s like a big symphony orchestra. Thousands of us are playing together, coming out with one big beautiful song.” ■

Native Chicagoan Web Behrens has spent most of his journalism career covering arts and culture. His work has appeared in the pages of the Chicago Tribune, Time Out Chicago, Crain’s Chicago Business, and The Advocate and Chicago magazines.