By Dennis Polkow

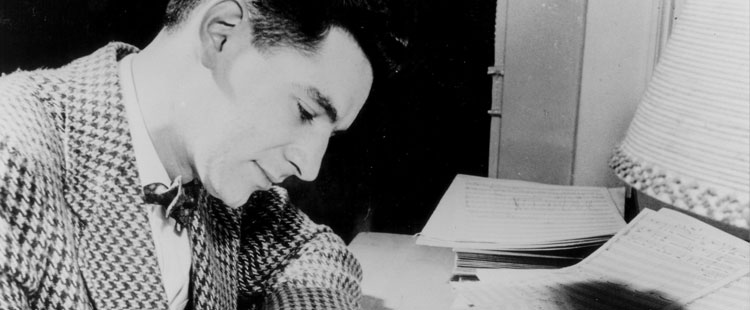

America’s most important music figure was many things to many people: conductor, composer, pianist, educator, author, television personality, activist, international bon vivant. But if you asked Leonard Bernstein how he self-identified, he thought of himself as a composer.

Over the past year and a half, the world has been honoring Bernstein’s centennial, which, by and large, has been a reevaluation of Bernstein the composer. That has meant abundant performances of his symphonies, choral works, chamber works, song cycles, ballets, and the like.

Bernstein’s Broadway shows, however, are in no need of reassessment, as works such as West Side Story and Candide have never fallen fully out of fashion.

Those works did the reassessing, breaking the boundaries of the form, particularly in terms of how elaborate and through-composed much of the music was and the extraordinary demands they made on the artists performing them.

Given that West Side Story is often considered the greatest musical ever written, it’s curious that its 1944 predecessor On the Town, the first show to unite choreographer Jerome Robbins and composer Leonard Bernstein, is done so infrequently.

Part of the reason is that the seamless line between music and drama achieved in West Side Story was still a work in progress within On the Town, the concept of which originated from the ballet Fancy Free. (That work was conceived by Robbins, who was so unhappy with its original composer that he simply showed up unannounced at Bernstein’s dressing room door in 1943 and managed to persuade him to compose the music.) That pedigree is never far from the surface of the show, as dance tends to intrude on the narrative, such as it is, and often for its own sake.

The score is meticulously well-crafted, but Bernstein was still in search of his own stage style, the music often coming off as Gershwin-meets-Shostakovich. When MGM made the film version, most of Bernstein’s score was gutted as being too “operatic” and replaced with new material by the studio’s house tunesmiths. Given the popular success of that film with its Frank Sinatra–Gene Kelly pairing, people often expect to hear the non-Bernstein movie tunes in stage productions.

On the Town, as it was originally conceived 75 years ago, was a wartime view of how to cram a lifetime of experiences into a 24-hour shore leave. Three sailors meet three women in “New York, New York,” of course, but time is the enemy as everyone knows that the guys will all be sailing off to God knows where, perhaps never to return, in less than a day. Instead of that being dealt with in a serious manner, Betty Comden and Adolph Green—whom Bernstein insisted be involved with the show—give us vaudeville-like comedy in the book and lyrics that were quite risqué for 1944: women flirting with men quite openly and sailors who have barely left home trying to grow up in a hurry while experiencing the Big Apple, all with the clock ticking. It was remarkably contemporary and effective in its day as a diversion from World War II, but it instantly became a period piece at the end of the war; sailors were still on leave, to be sure, but they were no longer heading off into a life and death struggle.

Bernstein presiding over a West Side Story rehearsal, with Carol Lawrence, who played Maria, at his left and lyricist Stephen Sondheim at the piano.

Wonderful Town followed a similar theme nine years later, as two sisters from “Oh, why oh, why oh, did I leave Ohio” decamp to New York in search of fame and fortune. Like in On the Town, dance is a central element in Wonderful Town, with Bernstein’s music increasingly eclectic, adaptable, and central to the drama. There is even an explicit Latin jaunt that foreshadows West Side Story in “Conga” in a dance with Brazilian cadets.

Bernstein wrote songs and choruses (both the music and the lyrics) and other incidental cues for a would-be musical of Peter Pan with Jean Arthur and Boris Karloff, but much of Bernstein’s music was again cut, with only five of his songs used in the 1950 Broadway production. Bernstein was so displeased that he turned down the opportunity to collaborate on a film version that theoretically would have used more of his score.

Although often staged as a musical, Bernstein called 1952’s Trouble in Tahiti a “one-act opera in seven scenes.” (Bernstein protégée Marin Alsop conducts soprano Patricia Racette and Tony-winning baritone Paulo Szot in the star roles for two performances at Ravinia on August 22.) This satiric “battle of the sexes” in mid-century suburbia is operatic in that it is through-composed with arias such as “There Is a Garden” calling for classically clarion sound and flexible vocal technique. Yet the commercial jingle style of the jazz-like vocal trio (soprano Michelle Areyzaga, tenor Nils Nilsen, and baritone Nathaniel Olson, all alumni of Ravinia’s Steans Music Institute) is as at home in the theater—Tahiti was mounted on Broadway in 1955—as in the opera house. Its dedication was to composer-lyricist-librettist Marc Blitzstein (A Cradle Will Rock), who, ironically, had led Bernstein down the path toward musical theater. Trouble in Tahiti ultimately received an operatic sequel that is less frequently performed, 1983’s A Quiet Town.

Marin Alsop returns not only as curator of Ravinia’s Bernstein celebrations in 2019, including the command encore of Mass, but also to conduct the festival’s first complete performance and staging of Bernstein’s Trouble in Tahiti.

Some of the music in A Quiet Town had been part of the only Broadway flop of Bernstein’s career, 1976’s 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue; it closed after only seven performances without a cast album even being recorded. Other music from that show became part of Bernstein’s 1977 Songfest, which celebrated the bicentennial of the United States through 12 song settings of 13 poems by American writers. Bernstein himself conducted the work at Ravinia with the National Symphony Orchestra in 1985, and a chamber orchestra version, which was premiered at festival on the Fourth of July 2013, was reprised at Ravinia on June 20 by six more RSMI alumni singers, with each of the original verses read by Chicago-based poets selected by The Poetry Foundation.

Bernstein wrote only one original film score in his entire career, for 1954’s Oscar-winning On the Waterfront. (David Newman will conduct the Chicago Symphony Orchestra performing the score live with a screening of Waterfront on August 9.) Even that was not something Bernstein had wanted to do, but during a screening of the unscored film arranged by director Elia Kazan, he was so taken with Marlon Brando’s performance that he found much of the music came to him while he was watching.

The ongoing development in Bernstein’s stage work can be heard in the Waterfront score: the love music for the film’s couple, Brando and Eva Marie Saint, prefigures music for Candide, and the heavily percussive and energetic brawl music is a precursor to “The Rumble” in West Side Story.

In 1955, Bernstein also wrote eight a cappella choruses used as interludes for the Broadway version of Jean Anouilh’s The Lark. Telling the story of the trial and execution of Joan of Arc, Bernstein used it as an opportunity to set four sections of the Roman Catholic Mass, an idea he would greatly expand a decade and a half later into 1971’s eclectic Mass, commissioned by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis for the opening of the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC. (Mass was the centerpiece of Ravinia’s 2018 celebrations and is receiving an encore performance by popular demand, with Alsop conducting the same 275-strong forces of singers and instrumentalists, from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra to the Highland Park High School Marching Band and Chicago Children’s Choir to the “Street Chorus” and Szot as the star Celebrant, on July 20.)

Based on the Voltaire novella that lampooned 18th-century optimism, Candide was written for Broadway in 1956 and ran a mere 76 performances, although the magnificent original cast album and the emergence of the show’s overture as a perennial symphonic staple have kept the show musically popular, as have such songs as the torturous coloratura romp “Glitter and Be Gay,” the infectiously clever “The Best of All Possible Worlds,” and the spine-tingling and poignant “Make My Garden Grow.” (The Knights will perform a two-hour staging of Candide, directed by Alison Moritz and starring Met Auditions–winning tenor Miles Mykkanen in the title role, at Ravinia on August 28.)

Miles Mykkanen (standing) will star in the title role of Bernstein’s Candide alongside Sharleen Joynt (pink costume) as Cunegonde in Ravinia’s first complete and fully staged production of the comic operetta, directed by Alison Moritz and performed by The Knights.

Harold Prince oversaw revisions of the work in the early 1970s that replaced the original book, both a one-act Broadway version and a two-act “opera house” version that was further revised in 1982, which the Lyric Opera presented with Prince as director in 1994. Prince thought the original Candide was too stuffy, so he sought to make it a bawdy comedy rather than the cerebral satire it originally was.

Bernstein himself had allowed but had nothing to do with these revisions, where half of his music ended up on the cutting room floor and the rest reordered. “In trying to eliminate what was admittedly a confusing book,” Bernstein told this writer in 1985, “the adapters also began tinkering with lyrics and where particular songs should be heard in the show, eliminating the overall musical architecture of the work, at least as I imagined it, and also tipping the work in too comedic of a direction.” The composer set out to correct this with his own “final revised version” of Candide, which he completed in 1988 and recorded in 1989.

Given that Bernstein had already determined to use opera singers for that recording of Candide, which he had also done with West Side Story in 1984, that conversation turned to whether he considered Candide to be an opera rather than a musical. “Ha! Neither one!” he exclaimed. “It’s the one operetta I’ve written. That is to say, it is much closer in style to Die Fledermaus than it is to Guys and Dolls.” Bernstein gave similar consideration to 1957’s West Side Story, which some would consider to be the great American opera rather than its greatest musical. (The 10-time Oscar-winning 1961 film version will be shown on July 12 with the CSO performing its score live, again with Newman conducting.)

“I have never written an opera,” Bernstein insisted. “I’ve always wanted to, but I’ve never done it. Somehow, everything I’ve done [of a vocal nature] has ended up leaning more toward musical theater, even though there are always strong operatic elements. Not that I haven’t tried. West Side Story came close. But ultimately, the most dramatic moment of the show—where Maria points the gun at all of the surviving Jets and Sharks who have shattered her love and her world—was left to be spoken. I tried and tried to make that speech an aria, but it just would not come off.”

Was there an opera in Leonard Bernstein? “Yes, but Bernstein the composer is held captive by Bernstein the conductor,” he assessed in July of 1985. “You have to set time aside to compose, and you can’t count on the fact that if you do set time aside, you’ll come up with something. Conducting is much more practical, especially for an old man. Plus, I love the instant joy that making music gives both me and an audience. Being a composer is the opposite of all that. It is a lonely existence. But before I pass from this earth … I would love to write an opera on the Holocaust. That is something that I must do, something that I feel ordained to do.”

Though Bernstein would pass on October 14, 1990, not having met that calling, he nonetheless left a heavenly host of music theater. ▪

Award-winning veteran journalist, critic, author, broadcaster and educator Dennis Polkow has been covering Chicago-based cultural institutions across various local, national, and international media for more than 35 years.