By John Schauer

All through the month of June, Turner Classic Movies featured films of Audrey Hepburn, and as I watched them—some for the first time, some for the umpteenth—I fell in love with her all over again. I know everyone is entitled to their own taste, but in this instance, it’s fair to say that if you don’t count Audrey among the all-time great movie stars as well as one of the most beautiful women ever to have walked the earth, there is something wrong with you.  She was perhaps at her most radiant in My Fair Lady, for which she was robbed of an Academy Award nomination primarily because she didn’t do her own singing. Totally unfair. But it reminded me that in one iconic instance, her own singing voice was not only used in a film, but introduced an Academy Award–winning song.

She was perhaps at her most radiant in My Fair Lady, for which she was robbed of an Academy Award nomination primarily because she didn’t do her own singing. Totally unfair. But it reminded me that in one iconic instance, her own singing voice was not only used in a film, but introduced an Academy Award–winning song.

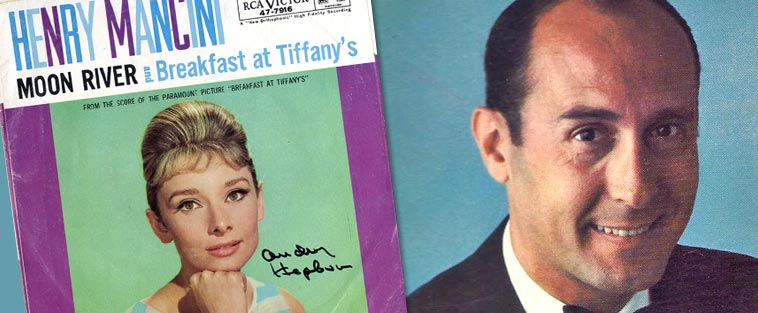

One of Hepburn’s most iconic movies, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, has always had two strikes against it becoming a favorite of mine. One is Mickey Rooney’s embarrassingly cartoonish performance as a Japanese man; the other is knowing how significantly Hollywood watered down Truman Capote’s original story, in which Holly Golightly (Hepburn’s role) is a prostitute and Paul (played by George Peppard) is a gay man—a far cry from the characters we see on screen. But the film boasts two major assets that make it unforgettable: Audrey looking drop-dead gorgeous in a wardrobe designed by Hubert de Givenchy, and that song. The song that gave its name to the entire August 6 concert at Ravinia celebrating the immortal works of composer Henry Mancini: “Moon River.” It’s not only one of the most beloved tunes boasting the “Best Song” Oscar credit, it probably extended the career of Andy Williams by several decades and became a universal anthem of romance, the ultimate “make-out” song. In Lifeguard, the 1976 film that made Sam Elliott a star, his long-lost high school sweetheart (played by Anne Archer) seduces him by playing an instrumental arrangement of it on her stereo. But America first heard it in 1961 when Audrey—strumming a guitar while seated on a windowsill, her hair wrapped in a towel—sang it with her own distinctive voice, winsome, wistful, and unforgettable.

Henry and AudreyMaybe Mancini, like me, had a thing for Audrey Hepburn, because music from three of her films is featured in Ravinia’s Mancini tribute. One of them I’ve only recently become acquainted with, Stanley Donan’s Two for the Road, in which Hepburn and Albert Finney portray a married couple struggling to salvage their marriage during a road trip through the French countryside. Described by film historian Robert Osborne as “romantic, remarkable, and somewhat disturbing,” it is said to have cemented Finney’s stardom, at a time when Audrey’s remarkable career was already at its zenith. Watching it for the first time, I found the two stars’ performances so mesmerizing that it took me a while to realize, to my surprise, that I was already familiar with the movie’s haunting theme song. Mancini’s songs had a way of insinuating themselves into our cultural fabric, whether you ever saw the movies they came from or not.

Henry and AudreyMaybe Mancini, like me, had a thing for Audrey Hepburn, because music from three of her films is featured in Ravinia’s Mancini tribute. One of them I’ve only recently become acquainted with, Stanley Donan’s Two for the Road, in which Hepburn and Albert Finney portray a married couple struggling to salvage their marriage during a road trip through the French countryside. Described by film historian Robert Osborne as “romantic, remarkable, and somewhat disturbing,” it is said to have cemented Finney’s stardom, at a time when Audrey’s remarkable career was already at its zenith. Watching it for the first time, I found the two stars’ performances so mesmerizing that it took me a while to realize, to my surprise, that I was already familiar with the movie’s haunting theme song. Mancini’s songs had a way of insinuating themselves into our cultural fabric, whether you ever saw the movies they came from or not.

Another Mancini song that became a classic was from another Stanley Donan opus, 1963’s Charade, one of my all-time favorite Hepburn films. The title tune appears three times in the film, in three different guises. It is heard in a hurdy-gurdy arrangement for a carousel in a Paris park, and again later in the somewhat saccharine mode most often employed by lounge singers who made it a standard (here done by a chorus while Audrey and Cary Grant float along the Seine River on an excursion boat). But it is in the opening credits that it is most electric and thrilling, floating over a pulse-quickening percussion track that later in the film underscores Audrey’s frantic attempt to elude her pursuers in a heart-stopping chase sequence that takes her from a Paris Metro station to the interior of the Paris Opera House.

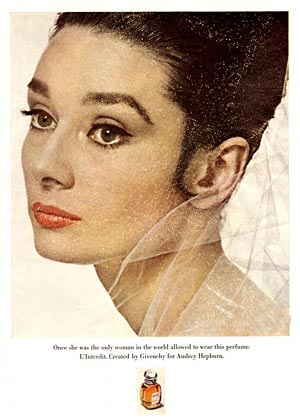

Twenty-four years later, Audrey filmed a similar chase sequence, this time through San Francisco’s opera house, in the made-for-TV movie Love Among Thieves. At the time it was being filmed, I was working in the PR department of San Francisco Opera, where I kept a gorgeous perfume ad from Opera News magazine with a stunning portrait of her on my bulletin board. One morning my supervisor walked by and casually commented, “You should have her sign that.” How could I do that, I asked, to which I got the astonishing reply, “She’s downstairs making a movie.” I grabbed the ad and flew to the mezzanine level of the house, where technicians and grips were arranging lights and cables. When I approached one and asked, “Do you think I could get Miss Hepburn to autograph this for me?” the grip answered, “Why not ask her yourself? She’s right over there.” I hadn’t even noticed her diminutive figure sitting on the stairs studying her script, and although I didn’t want to cause any disruption in the production, I hurriedly went over and blurted out, “Miss Hepburn, I’m a huge fan of yours and have had this photo in my office for years. Would you please sign it ‘To John’?” She looked up at me and simply said, “To John?” and then graciously signed it as I watched breathlessly.

I thanked her and ran back to my office before someone could throw me out of the production area, and proudly showed it to my co-workers. Everyone’s first question was, “What did she look like?” But I couldn’t answer; “I don’t know,” I stammered, “I was too excited to notice!” After all, this wasn’t just an opera star; this was a real star, a movie star, one of the biggest of all time. All I could think was, “Audrey Hepburn said my name!”—in that gorgeous, lyrical voice of hers, the same voice that introduced the world to “Moon River.”

I thanked her and ran back to my office before someone could throw me out of the production area, and proudly showed it to my co-workers. Everyone’s first question was, “What did she look like?” But I couldn’t answer; “I don’t know,” I stammered, “I was too excited to notice!” After all, this wasn’t just an opera star; this was a real star, a movie star, one of the biggest of all time. All I could think was, “Audrey Hepburn said my name!”—in that gorgeous, lyrical voice of hers, the same voice that introduced the world to “Moon River.”

—John Schauer