By Dennis Polkow

A significant debate in the performance of classical music that originated in the mid-20th century was whether or not to play Baroque-era music on 18th-century instruments or on their modern-day counterparts.

The aesthetic notion of the early music movement, as it became known, was to resurrect the contours and colors that composers of earlier eras originally intended by using the instruments that they actually knew, heard, and employed rather than with later, modernized instruments that they might have known.

Typical of the reactionary response against such originalist thinking was the view that modern instruments were the end product of a long Darwinian struggle of “survival of the fittest.” The thinking went that if Bach, say, had known the modern piano instead of its more primitive precursors, such as the harpsichord and clavichord, he surely would have preferred it.

Perhaps, Baroque purists argued, but knowing and writing for different instruments would surely have necessitated writing different music.

Two movements representing these views climaxed virtually alongside of one another mid-century, both particularly associated with music of Bach: the original/authentic instrument approach, and the modern instrument approach, the latter particularly espousing use of the piano for music originally written for harpsichord and clavichord.

In 1953, members of the Vienna Symphony, including cellist (later also conductor) Nikolaus Harnoncourt and violinist Alice Hoffelner (the two musical bedfellows would later marry), founded Concentus Musicus Wein after years of research into the performance practices of the Baroque and Renaissance eras. CMW ultimately sought to perform and record on original and authentic (“period”) instruments, but this came with a significant challenge. Surviving Baroque violins, for instance, would by and large have been modernized with the addition of a chin rest, a longer bridge, and synthetic strings and would be played with a larger bow. Restoring such rare and expensive instruments to their original state was experimental and risky.

Since a true, unmodified Baroque violin still in playable condition was a rarity, the best “period” instrument makers set out to copy a specific surviving instrument as closely as modern conditions would permit. The irony, critics claimed, was that most of these “authentic” instruments were actually newer than the modern instruments that they are supposed to predate.

Yet a modernized violin cannot begin to approximate the shimmering quality and clarity of line—with all the upper partials present—that one can hear from a gut-strung violin bowed with the infinite variety of tone that a Baroque bow is capable of producing, nor the light vibrato that is due to the absence of a chin rest. And the modern cello, which uses the floor as its sounding board with the help of a stick reaching from the bottom of the instrument to the ground, produces a louder and harsher sound than the much mellower Baroque cello, whose sounding board is the player’s own legs.

Performing on older instruments also employed techniques different from those used on their modern counterparts, techniques that had be learned by players who had already mastered modern techniques on modern instruments, and who often made their primary living performing on modern instruments.

Apollo’s Fire, the Cleveland Baroque Orchestra, is an American “reboot” of the early music principles that CMW had pioneered, and the ensemble is currently celebrating its 25th anniversary. Just as CMW had a connection to the Vienna Symphony, Apollo’s Fire originally had a relationship with the Cleveland Orchestra.

Perhaps no piece epitomizes the Baroque era more than Vivaldi’s ever-popular Four Seasons, the keystone of the Ravinia-debut July 27 concert by Apollo’s Fire spotlighting the composer that ensemble founder, artistic director, harpsichordist, and conductor Jeannette Sorrell calls “the rock and roll composer of the 18th century.”

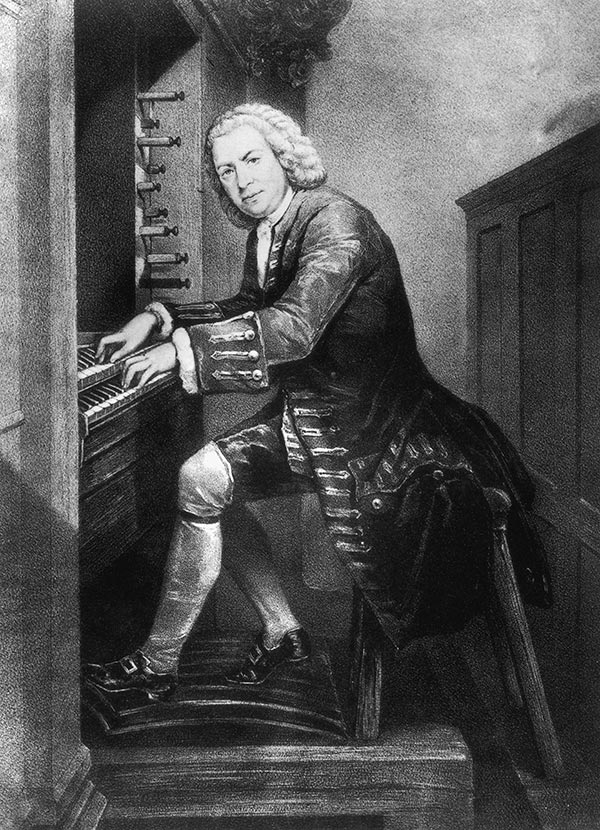

A no-less-popular work is, for better or worse, the poster child of the modernist approach to Baroque music. Count Keyserlingk, the Russian ambassador to Saxony in Bach’s day, who suffered from insomnia, had asked Bach to compose a series of variations on an aria to be performed over and over again by his harpsichordist—and Bach’s student—Johann Theophilus Goldberg. Whatever effect these “Goldberg Variations,” as they became known, may have had on the poor count, they may be considered a dismal failure in that they have kept audiences not only awake, but at the edge of their seats for centuries since.

For many, Canadian pianist Glenn Gould’s groundbreaking 1955 recording of the “Goldberg Variations” on a modern grand piano has been the standard by which all other performances are measured, even if digital technology has revealed not only Gould’s music making in sharper detail, but also his groaning, whining, and singing along with himself, phenomena that, in the static-filled days of vinyl, could mercifully be drowned out. It became fashionable to bash Gould when the early music movement was first gaining ground, but enough time has now passed that he can be appreciated for what he created: extraordinary recordings of an extraordinary, though eccentric pianist.

Angela Hewitt, another Canadian who has made Bach on the modern piano a specialty, has recorded all of Bach’s keyboard music—but with fewer eccentricities—and is presenting the complete “GoldbergVariations” at Ravinia on July 17. Whereas Gould preferred the studio environment and became so reclusive that he would no longer play in public, Hewitt prefers to tour widely in addition to recording.

There are various approaches to performing the “Goldberg Variations,” most having to do with tone color, an element largely determined by the performer’s choice of instrument. Bach’s own was the double-manual harpsichord, complete with stops and couplers to vary the sound, but recordings of the work have included versions for string trio and harp.

To perform the “GoldbergVariations” on the modern piano, the most practical problem is that the variations entail a constant collision of the performer’s hands as they move back and forth across a single keyboard. It’s a visually arresting virtuosic phenomenon that has always been an aspect of the work’s appeal for audiences, but also an enormous physical and mental challenge for the pianist, who has to develop gargantuan powers of simultaneous coordination and contemplation, wherein not only fingering has to be precisely worked out, but hand movements have to be carefully choreographed.

Whatever the instrument, the most common interpretive approach is to present the work in an abstract and episodic manner, taking deliberate pauses between the 30 variations and using the bookend Aria as points of departure and arrival for its principal structure. Hewitt, however, prefers to take every repeat of each variation (except in the Aria itself, which forms the basis of the variations), and by mostly offering contrasting details within those repeats, many of the variations take on a decidedly sonata-like feel with repeats often serving as a kind of recapitulation much the way they would in Haydn or Mozart.

And yet, by often gliding from one variation right into another virtually without pause, Hewitt manages to construct continuous building blocks of Bach that, together with contrasting repeats, make for larger segments of music that at times remind us of the way that Beethoven would use the same technique decades later.

Instead of seeing Bach as the culmination of everything that preceded him (i.e., the usual approach), Hewitt refreshingly reminds us that Bach was also the forerunner of all that followed him. Yes, we know that, of course—but how often is Bach’s music actually performed in such a way that we can actually hear that directly for ourselves? There are times when, in Hewitt’s hands, at least, you can hear Bach be not only a direct precursor to Classicism and to 19th-century Romanticism, but even to late Liszt and Scriabin.

Should Gould’s, Hewitt’s, or anyone else’s Bach on the modern piano be confused with performing his keyboard music on the actual instruments that Bach wrote it for? Better they be viewed as transcriptions for the modern piano. But transcriptions that introduce the wonders of Bach to a wider audience have enormous value, and often serve as entry points into Bach’s original intentions. As legendary Polish harpsichordist Wanda Landowska used to boast, “You play Bach your way, I’ll play him his way.”

Veteran award-winning journalist and critic Dennis Polkow is columnist for Newcity Chicago and a Chicago correspondent for London-based Seen and Heard International.