By John McDonough

“Life is great,” said Ramsey Lewis on an April afternoon, socially distanced in his Streeterville home in Chicago.

Our conversation was originally to be of the face-to-face variety, but with faces having become a focal point of health awareness, we instead took to the phone. But, of course, we weren’t alone in adjusting our plans—even nearby North Michigan Avenue was conspicuously depopulated, like the eerie boulevards in the last scenes of On the Beach. No urge even for a spring walk? “I’ll wait a couple of months,” Lewis said. “I’ve got plenty to read, much music to play. I’m happy.”

At 85, Lewis is now enjoying the freedom of retirement. He stepped away from touring nearly two years ago, leaving behind the roars of recognition he would hear when playing the first bars of “Hang On Sloopy.” No more audiences, no more applause. Why, I wondered.

Three words, he replied: “No more travel.”

“Playing the piano anywhere in the world has always been fun for me,” Lewis continued. “But as I got older, I began to hear, ‘Your room is not ready, sir. It will be another hour.’ Then an hour later: ‘It’s still not ready, sir. Would you like to have dinner on us?’ And then there were the airports. ‘The plane is going to leave at gate 82,’ followed by, ‘The plane’s delayed, and it will leave from gate 149.’

“One day I looked at my wife and said, Why are we doing this? So we decided not to do it anymore. Flying today is like going from Chicago to London on a bus. The price of playing piano became too high.”

Little Ramsey’s Got Something

Lewis can barely remember his life without the piano. According to press bios, he started at the age of 4, a claim that raises the question of whether he chose the piano or it chose him. He confesses that it may be a slight exaggeration.

“I was probably closer to 7 years old,” Lewis says. But the choice was his, he confirms, though one very much influenced by his sister, Lucille, who was four years older. “Whatever my sister did, I usually liked doing too,” he says. “One day, Dad told her that she should take piano lessons. She wasn’t too excited about that, but I said, Hey, I want to take lessons too. The teacher was the organist at the AME [African Methodist Episcopal] Church, Ernestine Bruce. After a few months, she told my parents that Lucille’s talents were not in music. ‘But little Ramsey,’ she said, ‘I think he’s got something.’ After two or three years, she said she’d taught me all she could. So I went to the Chicago Musical College.

“Fortunately, I was assigned to Dorothy Mendelsohn, and she changed my whole life. She gave me something to learn, and I thought I’d learned it—I knew the notes. But she would say, ‘Ramsey, make the piano sing.’ Really, I thought. The piano, sing? We traded places, and she played the same passage. And it was so beautiful. ‘You see,’ she said, ‘you must make the piano sing.’ I never forgot that lesson. It’s stayed with me to this day.”

“I became enraptured by the piano. My parents would no longer say, Did you do your practicing today? Instead it became, You’ve been practicing too much; do your homework.”

With musicians who began at such a young age, there’s often the question of whether or when there was a eureka moment that marked a Rubicon on the path to elevating their avocation, when suddenly they realized the instrument had become an extension of their thinking. Lewis considered for a moment.

“Yes, when I was 12,” he concluded. “That’s when the piano first started speaking to me. That’s when I found I had a real relationship with this instrument that’s close and personal. That’s when the notes started to say hello to me, and me to them. I became enraptured by it. My parents would no longer say, Did you do your practicing today? Instead it became, You’ve been practicing too much; do your homework.”

What was hard labor for his sister became a kind of bliss for Ramsey. Drudgery and discipline were instead delight and discovery. As he moved into adolescence, he was on what Malcolm Gladwell terms the “10,000-hour path to success.” He had not yet discovered Art Tatum, Teddy Wilson, or Bud Powell, nor even what kind of pianist he wanted to be. “Not then,” he says. “I just loved the music of the moment. I loved reading it, memorizing it, playing it. What it was wasn’t that important.”

For his 80th birthday, Ramsey Lewis included the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in his “music of the moment” as he made his long-awaited debut with his hometown band at Ravinia, premiering his Concerto for Jazz Trio and Orchestra, commissioned for the occasion by the festival.

So Lewis entered Wells High School on North Ashland in 1949 with a unique strength, like being a top athlete but even better. Overwhelmingly white and Polish, Wells had a deep curriculum in the arts—its alumni would later include Jerry Butler and Curtis Mayfield—and once a year the kids put on a musical. “At least two or three times a day,” Lewis recalls, “I’d be in class, and a kid would come in, whisper to the teacher, and she’d say, ‘Ramsey, they need you in chorus.’ A few hours later, same thing: ‘Ramsey, they need you in ballet.’ That’s how I went through high school. I recognized it was a strength that gave me a certain importance and self-confidence.”

Let’s Start with a Blues

For most teenagers, high school is when they begin seeing the world through their own eyes. The music they hear often imprints a generational identity that lasts a lifetime. How deeply was Lewis impacted by the pop voices of mid-century America—Patti Page, Frankie Laine, Perry Como, Vaughn Monroe, Eddie Fisher, the Ames Brothers? “Not at all,” he suggests. “I listened along with my friends, enjoyed it, but it didn’t leave much of an impression on me.”

Instead, he was introduced to jazz. “I was playing gospel piano on Sundays with a man named Wallace Burton, who was a few years older than I was,” Lewis remembers. “One Sunday, Wallace asked me if I wanted to play in his band. He’d heard me play gospel and classical, so he assumed that I could probably play jazz. He took me to a rehearsal and said, ‘Okay, Ramsey, let’s start with a blues in B-flat.’

“‘Ramsey, they need you in chorus’; a few hours later, ‘Ramsey, they need you in ballet,’ that’s how I went through high school. … Jazz was as daunting as classical—more so because of the technique of improvisation.”

“Well, I didn’t know anything about the blues. ‘Okay,’ Burton said, ‘we’ll play this thing on ‘I Got Rhythm.’ Again, I didn’t even know the rhythm changes. He asked if I knew any standards at all, and I didn’t. I figured that was it. He told me that I had to learn this music. It was what jazz was all about. So he invited me to his house and showed me what’s up.” Burton not only introduced Lewis to the jazz songbook, he showed him the miracles that musicians like George Shearing, Art Tatum, Oscar Peterson, and Erroll Garner could perform with it. To Lewis, it was a revelation.

“Whoa, I thought. Really!” Lewis said, laughing as he remembered this moment of truth. “It was a kind of ‘aha’ moment for me. Jazz was as daunting as classical—more so because of the technique it took to master the harmonic basis of improvisation. Jazz was more than the blues and ‘I Got Rhythm.’ ”

Along Came Daddy-O

The Korean War broke up the Burton group, but the rhythm section stayed on—bassist Eldee Young and drummer Ozzie Riddle—and became the basis of the first Ramsey Lewis Trio. They played around Chicago for a couple of years when they could; at 20, Lewis looked too boyish to be a jazz musician. “I went to the Blue Note once and I had an ID,” he remembers, “but they still wouldn’t let me in.” Five years later he would record an album there. After Korea, Redd Holt joined on drums, and the trio became a working group.

“And then came Daddy-O Daylie,” Lewis said.

“Ah, Daddy-O,” I interjected. “I remember listening to him after Jack Eigen signed off from the old Chez Paree [nightclub]. I heard my first Milt Jackson [recordings] on his show.”

“There you go,” he smiled. “You know what I’m talking about.”

What I’m talking about is Holmes “Daddy-O” Daylie, the hippest jazz jock in town and the self-described “host who loves you the most.” He had grown up in Chicago and developed a gift for rhyming jive patter while shooting hoops on the road with the Harlem Globetrotters. Dave Garroway discovered him in a local bar plying his rhyming raps and convinced him he belonged on radio. By the mid-’50s, Daddy-O Daylie had become the town’s most famous hipster, playing hardcore bebop to insomniacs on WMAQ, whose clear-channel signal reached as far as New Orleans and Dallas after midnight. Whatever it was, Daddy-O knew where it was at, including Ramsey Lewis, whose fledgling trio he picked up on early. Pretty soon, he was a kind of unofficial manager-publicist for the trio, mentioning it often on his program. But there were no records he could play yet.

The first recorded incarnation of the Ramsey Lewis Trio featured bassist Eldee Young (back) and drummer Redd Holt (left).

“He got us a gig at Stelzer’s Lounge, an upscale restaurant in [the] Lake Meadows [neighborhood],” Lewis recalls. “And one night he comes in and asks if we’d like to make a record. ‘Well, yeah, of course,’ we said.”

Play More in the High Keys

Daddy-O knew Leonard and Phil Chess, who owned a stationery shop on the 1400 block of South Cottage Grove Avenue. At that time, in 1956, they had a music room with a broken-down piano in the back where they made blues records, and the Chess brothers had just begun branching into jazz with Ahmad Jamal on their newly formed Argo label.

“So Daddy-O took us there, and we played for Phil Chess,” Lewis continues. “He said, Hey, you guys are pretty good. Then he calls in the back room for a guy named Sonny to come out. ‘Listen to these guys play.’ And Sonny says, Yeah, pretty good. So on the strength of that, we got our first record shot. Daddy-O would then play our stuff on the air, and that got us a lot of work.”

Recording for Argo—renamed Cadet in 1965—was refreshingly free of bureaucracy. Most of the trio’s records were made in the second-floor studio at 2120 South Michigan Avenue, where the company moved in 1957. (Today the building is on the National Historic Register.) “Phil would come up when we were recording,” Lewis says. “When we’d listen to the takes, he was always telling me, ‘Ramsey, play more in the high keys, please.’ That was about the extent of his involvement as a producer.”

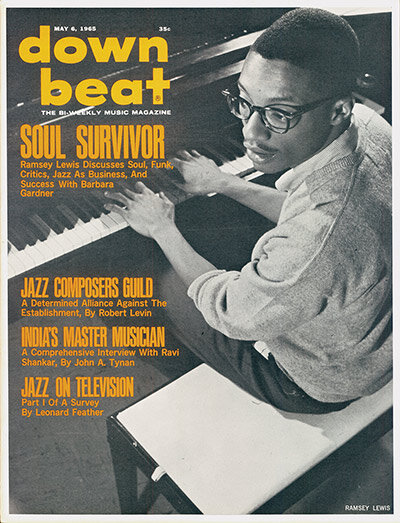

Lewis’s first DownBeat cover feature came just days before he recorded what would be his first Grammy winner, “The ‘In’ Crowd.”

There would be a procession of singles and albums—Christmas songs, spring songs, bossa nova songs, even a country album. “Country music is not far from the blues, in a way,” Lewis says. “But jazz musicians don’t go there very often. It’s a cultural thing, I think. Jazz has always been a big-city sound, and there’s a little bit of the rural heritage that’s still clung to country music for some jazz musicians.”

Lewis would remain with Chess for the next 16 years. But since the days of Jelly Roll Morton, the history of jazz and blues is abundant with sordid stories of white-owned record and publishing companies exploiting black artists. But Lewis never felt that specter at Chess. “I found it a very good relationship. I think my friendship with Daddy-O may have had something to do with them coming clean with us on our sales and such. On our first couple of albums, we had had some songs that we put with Arc Music, the publishing company Chess started in 1953. Then a light came on that I could be getting that money. That’s when I formed my own publishing company. But there were never any problems. In fact, I was one of the few, if not the only one, who Leonard invited to his home in Glencoe to meet his family.”

Somewhere North of Fargo

That visit to Glencoe brought Lewis closer to Ravinia than he had ever been in his life. Remarkable as it may seem, though a native Chicagoan, Lewis had never actually been to Ravinia in his life. The first Pavilion concert he ever attended was his own in July 1966.

“I used to hear about Ravinia in the ’50s,” he says. “But to me it seemed like it was somewhere north of Fargo. I was only 19 or 20 and didn’t drive a car. I saw music in places like the Birdhouse, the Sutherland Lounge, and the Blue Note downtown. To a North Side city kid like me, Ravinia was a playground of suburbia. How was I ever going to get up there?”

The first Ravinia concert Ramsey Lewis ever attended was his own in July 1966.

In a limousine, it turned out. His ticket would be an unexpected, run-away hit for Argo that made him a national star in 1965. Incredibly, however, “The ‘In’ Crowd” was a record that almost never got made.

“In those days, the trio had its serious songs,” Lewis says. “But we also got into the habit of putting in a couple of fun ones. ‘In Crowd’ was a fun song, a little rhythm tune by Billy Page that Dobie Gray was doing. We started using it in our sets for variety, but we never recorded it or had any expectations of it. Nor did Chess. What’s interesting is that we were recording live in a place called the Bohemian Caverns, a jazz room in Washington [DC] where guys like Dexter Gordon and Sonny Stitt hung out. The clientele were students of bebop and modern jazz. They would sit very seriously with their chins in the hands and look like they’re studying the music.

“Maybe that’s why I forgot to call the tune. ‘In Crowd’ didn’t seem right for this audience. The set was about over and I had started to announce an intermission when I heard Redd saying, ‘Hey, Ramsey, not yet. We didn’t do “In Crowd.” ’ Oh yeah, I thought, one more. So we went into the tune and—my god!—these people started standing up at the tables, dancing, jumping around, laughing, shouting, and clapping. When it came out, a lot of people thought it was dubbed in to spike the excitement. But it was all real.”

“Yeah,” he muses after a pause, perhaps having contemplated the existential uncertainty of a random universe. “I wouldn’t want to have missed that one.”

Early in 1966, he got “the call.” In a Ravinia season that would include Ella Fitzgerald and Dave Brubeck, Lewis made his debut July 27. It would be the first of more than 40 appearances he would log, ranging from trio concerts to collaborations with the Joffrey Ballet and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra—more than any headliner in Ravinia’s history outside of its resident conductors and such longtime classical guests as violinist Itzhak Perlman, pianists Leon Fleisher and Misha Dichter, and the late cellist Lynn Harrell.

Ten minutes from Lewis’s 1966 Ravinia debut set would become a central part of WBKB-TV’s The Sound of Ravinia telecast special later that summer.

“It was heady,” Lewis recalls. “Being invited to play at Ravinia was prestigious. I enjoyed that my friends and relatives were impressed with my being there. It wasn’t like the Chicago Theatre or Radio City. Those were show-business venues. Ravinia was a sanctuary of pure music.”

Much of that prestige lingered from an older, staider Ravinia, where a rare jazz could still confer a kind of “legitimacy” to the music. In those days, Ravinia was covered as thoroughly in the society pages as the arts sections. To Chicago Tribune critic Claudia Cassidy, it bespoke a “charmed life” of wealth and culture. But by 1966, a decade of increasingly frequent incursions of jazz and folk music was encouraging Ravinia’s willingness to expand its audience. Through the ’60s and beyond, Lewis would take the stage often and see both jazz and Ravinia evolve in unexpected ways.

The Ideal Candidate

“For me, jazz has always been a people’s music,” Lewis reflects. “When people pay their money to see you, you have to respect of that. You might play some outside stuff, and your audience will accept that to a degree. But you can’t finish your set without playing what they want to hear. Give them something.”

Over the years, Lewis developed an intimate understanding of the Ravinia audience. So after Gerry Mulligan stepped down from a two-year stint as artistic director of jazz programming in 1992, then–Ravinia CEO Zarin Mehta found the ideal successor right in his own backyard. Soon after Lewis took over in 1993, Jazz at Ravinia grew to virtual jazz festival within the larger summer season. His mission was to expand Ravinia’s reach beyond the traditional suburban audience. “Slowly that began to [happen] with Zarin Mehta,” he says. “And it got even better when Welz Kauffman became CEO in 2000. He said we’ve got to draw people from all over the area. Because of Welz, the jazz audience started coming from the south, west, downtown, truly all over.”

Lewis and choreographer Donald Byrd enjoy a break in a rehearsal for the Joffrey Ballet’s premiere of To Know Her, which featured music by Lewis.

Kauffman had an even more direct impact on Lewis’s musical growth. “He encouraged me to really develop my writing,” he says, “first with my trio and a ballet [To Know Her, 2007, for the Joffrey Ballet], and then with the Turtle Island String Quartet [Muses and Amusements, 2008] and the CSO [Concerto for Jazz Trio and Orchestra, 2015]. Hello! Welz was always trying to give me that little boost, but always gentle. He never pushed, just made suggestions. He was a late-career mentor to me.” Another major milestone was the premiere of Lewis’s symphonic poem Proclamation of Hope, commissioned for and premiered at Ravinia for its celebration of Abraham Lincoln’s bicentennial in 2009.

With a $400,000 budget to work with, Lewis brought a whole new generation of headliners to Ravinia over the next decade. He mixed Keith Jarrett, McCoy Tyner, Roy Hargrove, Pat Metheny, David Sánchez, Ed Wilkerson, Ari Brown, and Randy Weston with veterans such as Oscar Peterson, Stéphane Grappelli, Sonny Rollins, Dave Brubeck, Benny Carter, and Herbie Hancock.

When Lewis took up the reins as artistic director of Jazz at Ravinia in 1993, it also marked his 15th performance at the festival.

In 1996, the Tribune’s Howard Reich wrote, “Jazz at Ravinia already towers over the Chicago Jazz Festival as far as quality, creativity, and budget are concerned. … In so doing, [it] has taken on musical and education dimensions unimagined at the Chicago Jazz Festival.”

“Ravinia today is not what it was 50 years ago,” Lewis reflects. “It had to get here and develop through the various artists that have widened the scope of ‘Ravinia programs.’ I saw my role as introducing musicians Ravinia audiences would appreciate—or learn to appreciate—and to widen their knowledge of what’s available in jazz. That’s what I tried to do. And the crowds got bigger for jazz, which was unheard of since the days of Benny Goodman, Louis Armstrong, and Ella Fitzgerald.”

She Could See What I Was Thinking

For Gerry Mulligan, being artistic director of Jazz at Ravinia had given him the chance to sit in with his favorite players. Audiences loved it. But Lewis wasn’t so tempted to join his guests on the festival’s stage.

“It depends on the venue. A club atmosphere is much more relaxed,” Lewis says. “But the concert stage is different, not only because of time constraints but the formality that prevails when a large audience is present. You risk disappointing too many people if it doesn’t go well. A place like Ravinia discourages that kind of spontaneity because expectations are high. And for many jazz artists, Ravinia is a major concert gig, not the third set in a club. I felt the artist should have control over their presentation, make their point according to plan. I didn’t want to interfere with those prerogatives.”

I was skeptical. “Never?” I asked. “Come on.”

“Well, once,” Lewis said. “Dave Brubeck was ending his set with a blues. I was standing in the wings with his wife, and he was really getting into it. I looked at her and she could see what I was thinking. ‘Go on, do it,’ she said. So I went out there. He sees me, smiles, and moves to the right of the bench to give me space. And we had so much fun playing four hands. But that was about the only time.”

Ten years ago, Lewis made a surprise guest appearance during Dave Brubeck’s set at Ravinia, joining his fellow legendary bandleader and composer at the piano.

He reminisced about others he brought to Ravinia over the years: Stéphane Grappelli (“He could make the violin sing.”), Oscar Peterson (“We sat down at the piano, and did he show me a few things!”), Billy Taylor (“He could play a whole concert with his left hand. That’s how developed it was.”), and Nancy Wilson (“I met her before she made her first record, and we were friends till the day she died.”).

I reminded him that all those artists are gone now, which led to the final question. The profile of jazz today at Ravinia is not what it was 20 years ago, but for good reason—the superstars of the music today are far fewer and mostly over 75 (Hancock, Corea) or retired. Is jazz replacing headliners of that stature fast enough to sustain itself on the concert stage?

Nancy Wilson made her own Ravinia debut just one week before Lewis, and they would share the Pavilion stage five times from 1991 until their final pairing on Lewis’s 75th birthday concert.

“You’re right,” he said. “Jazz has a serious shortage of headliners. This is partly because of fewer clubs, less jazz radio, fewer venues. The performance infrastructure in which a musician could build a name for himself has shrunk. When Herbie and Chick were coming up, they also had the chance to develop as sidemen and build some fame with major stars like Miles Davis or Stan Getz. When I was young, we came up through the ranks. There were a lot of things that could prepare you for a stage like Ravinia’s.”

“The music now struggles for relevance,” critic Nate Chinen recently noted. “In 1958, it was fighting for respect.” In a lot of ways, that fight was a lot more fun, Lewis suggests. It’s why he considers himself blessed.

“Believe me, these are different times, man,” he concludes. “But when I look back, I’m so glad that I lived my career at the time that I did. Everything has its time and place, and I was very lucky.”

A contributor to DownBeat and National Public Radio, John McDonough teaches jazz history at Northwestern University